Recommended

This blog is part of CGD and Refugee International’s #LetThemWork initiative and written in conjunction with Refugee Action. It is one of a series of blogs exploring the issues facing refugees’ economic inclusion within the top refugee and forced migrant hosting countries. All are being authored with local experts and provide a snapshot of the barriers refugees face and what the policy priorities are going forward. You can read a blog on the context of the ban here.

Every year, tens of thousands of people claim asylum in the UK, with many of them waiting years before they receive a decision. In the first year of their wait, asylum seekers have no legal right to work, and must survive on minimal government support. After this point, they can apply for the right to work, but available roles are heavily restricted.

This policy has detrimental effects for the asylum seeker and their family, their country of origin, and even the UK. Changing this policy could benefit the UK through a net gain of almost £181 million per year. The first part of this blog, available here, looks at why asylum seekers in the UK don’t have the right to work. The second part looks at the impacts of this ban and what a potential way forward might look like.

The impacts of the ban on asylum seekers

Many people seeking asylum in the UK tell Refugee Action that, if they could change one part of the system, it would be to lift the ban on employment. Asylum seekers say they want the ability to access the labour market, earn money, and use their skills. This is because the ban on the right to work is a contributing or compounding factor to other issues they experience.

Many are in poverty. The weekly government allowance is £5.66 per day (approximately US$7.72). Refugee Action supports asylum seekers who say this amount is not nearly enough to cover essentials such as food, medicine, travel, communication, clothes, and hygiene products. As one asylum seeker said:

“You can barely afford food and simple things like tampons are very hard to buy when you are an asylum seeker… It’s hard, it’s hard for everyone.”

People also do not like to be dependent on the state and want to contribute to their communities. Many asylum seekers come from countries that do not have a welfare system, so the concept of an allowance from the government is alien to them.

“People keep coming, trying to give you things… Come on, I have my hands. Let me work and get the things for myself. I can even help other people, I don’t need people helping me.”

Asylum seekers see the ban as a barrier to integration. In the early stages, it is one less opportunity for them to mix with the resident population, where they can pick up customs, learn English, and make friends.

Once they are granted asylum, many have spent long periods out of work, in which time skills and confidence have waned making it more difficult for them to find employment. Indeed, research in Switzerland has found that one additional year of waiting reduces the subsequent employment rate of refugees by 16-23 percent, and research across Europe has found exposure to a ban on arrival reduces eventual employment probability by 15 percent.

“I’m worried about my future job because of these five years that I lost.”

As asylum seekers wait for their case to be processed there is little to do, leading to boredom, hopelessness, and other detrimental impacts on mental health.

“I want to work because it gives me the feeling of being someone. I want to work because I don’t want to look back after five or 10 years and realise I did little except sit alone in a room and wait for a decision on my asylum claim.”

On their countries of origin

Without jobs, asylum seekers are also largely unable to send remittances home, adversely impacting families and communities in countries of origin. To calculate this impact, we looked at the average share of remittances received in the top 20 countries of origin for migrants in the UK. We then calculated the share of an average migrant’s income that is typically sent home by comparing the amount remitted to the median annual pay for all employees in the UK.

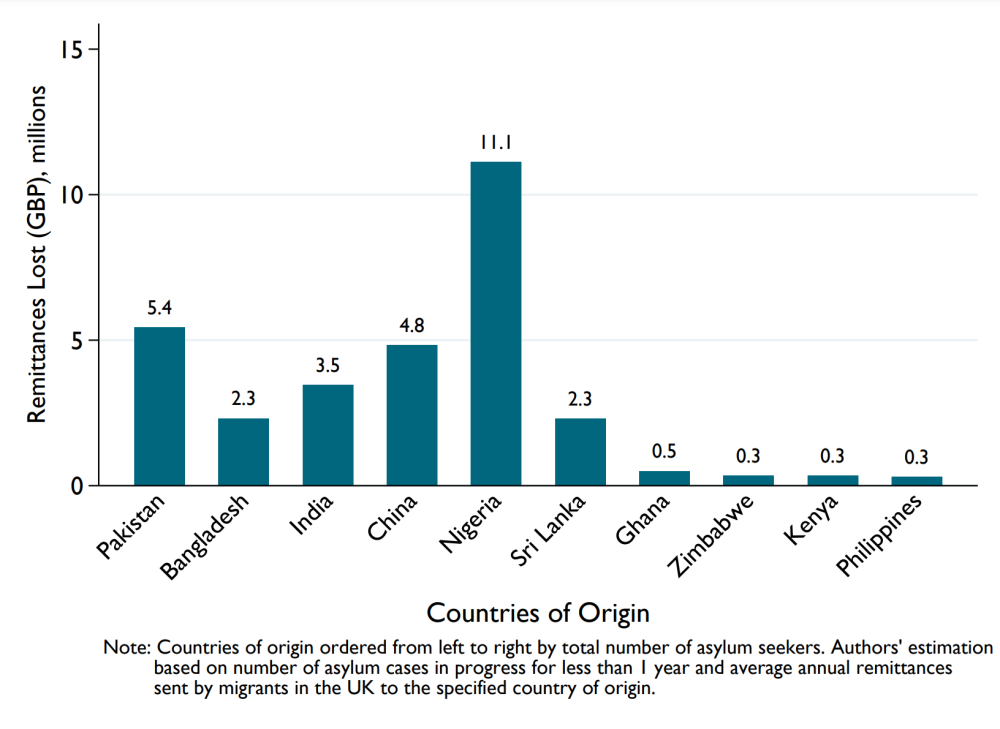

For people who have been waiting for up to 12 months for their claim to be processed, we calculated the remittances that would have been sent if they were allowed to work. Per our estimation, in 2018 alone, the ban cost countries of origin at least £31 million (approximately US$35 million) in forgone remittances. For families in Pakistan, the money lost amounted to £5.4 million; for families in Nigeria, £11.1 million was lost.

Figure 1. Amount of potential remittances that could be sent to countries of origin, if asylum seekers were allowed to work

Note: Author’s estimation based on number of asylum cases in progress for more than one year, and average annual remittances sent by migrants in the UK to specific countries of origin. Ordered by size of migrant population.

On the UK economy

The ban also has an adverse impact on the UK Treasury. This is largely caused by two factors.

Firstly, the government could save money it is currently spending on the asylum support system. As of September 2021, the government was paying asylum support to almost 68,000 people every week, as they wait for their claim to be decided. This is, of course, necessary, as the government has a legal duty to make sure people do not end up destitute. Secondly, the UK Treasury could be earning tax and national insurance payments on income earned by people in the asylum system if they are granted labour rights.

Based on these two factors, the #LiftTheBan coalition has calculated that the UK Treasury could gain £181 million a year (approximately US$240 million) if asylum seekers had the right to work. These calculations were based on 50 percent of people seeking asylum finding work that paid the average UK income of £30,400. The coalition’s top-end estimate is the UK Treasury could save as much as £650 million.

What does the future hold?

The issue has attracted much political and public debate in the last year. Despite support from prominent Conservative politicians such as Justice Secretary Dominic Raab and Business Secretary Kwasi Kwarteng, efforts to amend the government’s Nationality and Borders Bill in the House of Commons—by inserting a clause that would codify an asylum seekers’ right to work— were rejected.

On December 8, the Home Office released the results of their three-year review of the ban, stating that they would not be changing the policy. Tom Pursglove, Parliamentary Under Secretary of State, said:

“In light of wider priorities to fix the broken asylum system, reduce pull factors to the UK, and ensure our policies do not encourage people to undercut the resident labour force, we are retaining our asylum seeker right to work policy with no further changes.”

Yet support for lifting the ban remains widespread. Repeated polling by the #LiftTheBan coalition, British Future, and MRP polling has revealed that more than 70 percent of the public and 67 percent of business leaders support the right to work for asylum seekers. Challenges to the ban have been raised in the High Court, with cases in December 2020 and October 2021 finding the ban to be unlawful and discriminatory.

In its 2021 annual review, the government’s Migration Advisory Committee recommended that Ministers should again review the ban, adding people should be given the right to work after six months and not be constrained to the Shortage Occupation List. The Committee also called on the Home Office to release evidence that the right to work acts as a “pull factor.”

In January 2022, the Nationality and Borders Bill will be debated in the House of Lords and the amendment clause mentioned earlier, including the right to work, is expected to be added. Given the overwhelming economic benefits that lifting the ban would provide asylum seekers, their countries of origin, and the UK, hopefully the House of Lords will move this debate forward.

Note:The #LiftTheBan coalition is made up of more than 250 UK organizations, including businesses, recruiters, think tanks, faith groups, trade unions, and refugee charities. Refugee Action is one of two organizations in the secretariat, the other being Asylum Matters. This blog was updated on 1/25/2022 to correct an error in the data.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Adobe Stock