Recommended

This blog post originally appeared on the Development Leadership Program’s website.

A few months ago, I had the great pleasure of giving a keynote address at the Research for Development Impact Network (RDI)’s 2019 Annual Development Conference, which focused on “Leadership for Inclusive Development.” This blog post, commissioned by the Development Leadership Program (DLP)—a sponsor of the conference—draws on the themes of my speech and goes beyond them. That speech is available here.

Development partners—donors, people who give out money to do good things, call them what you want—have been talking about “letting the driver steer” for longer than I’ve been driving (and I’m rapidly approaching middle age). But rarely has this gone beyond injunctions—beyond broad calls to put more power in local hands.

The pitfalls of donor reporting practices

Andrew Natsios, former head of the US Agency for International Development (USAID), has argued that donors suffer from Obsessive Measurement Disorder (OMD), the mistaken belief that things will get better just by measuring them. My research suggests he’s right – with USAID projects in Liberia and South Africa clearly suffering from the ailment, to the detriment of development impact. OMD is maybe best seen as part of a related ailment I’m making up just now in this blog post—Obsessive Measurement & Control Disorder (OMCD). It’s not just USAID—donors generally suffer from OMCD. Donors’ reporting and control practices undermine performance; they do this by prompting those closest to the ground to meet targets but miss the point—to focus on the quantifiable in a job that’s anything but.

Someone leading a development project experiences, absorbs, and comes to understand much more than can be summarized in quantifiable targets. If the targets are perfect summaries for the aims of the project—e.g., if the only thing the project cares about is, say, infant mortality, and we can measure that clearly—then the fact that so many important things aren’t quantifiable isn’t really a problem; those working on the ground can incorporate what they see (but donor HQ can’t) into their work, forwarding the measurable goal which can be seen from HQ. But most development work isn’t like that in practice; that is, most of the time a project has at least some objectives we can’t measure perfectly, or we’re worried about distortions—e.g., we don’t want improvements in infant mortality to come at the expense of care for the chronically ill, or by diverting resources from the education budget, etc. When those doing the work on the ground focus on donors’ OMCD-inspired numbers and process controls, they at times have to ignore part of what they judge to be true, to be the right way of going about their work.

If we care about local knowledge (and we should), we need to actually give people local control.

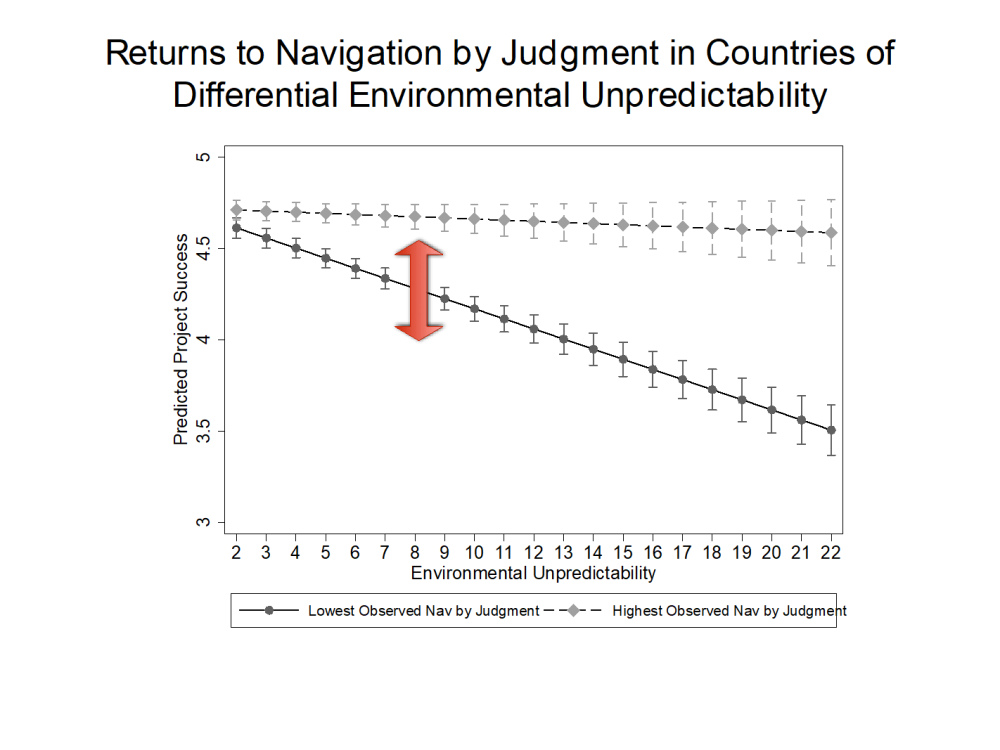

Donors: Getting more of what you want sometimes leads to less of what you want

“But,” worries the critic, “Who are you to define ‘success’? By what yardstick ought we measure?” My yardstick might differ from that of a given donor—so I choose to use theirs. That is, I use donors’ own ratings of project success, building a database of 14,000 development projects outcomes (data now public/downloadable from my website). I find that by donors’ own ratings, those donors with greater levels of OMCD see more of a decline in project performance as environments get more unpredictable (see Figure 1). You don’t have to come at this problem with some outside standard to, I hope, be convinced that OMCD is a problem.

Presentation slide 16, Honig talk at RDI Melbourne Conference, June 13 2019; drawn from Honig 2018, 2019

As a parent of a five-year-old I spend a fair bit of time in parks, watching my son and other kids play. A few weeks ago I saw something that reminded me so much of OMCD: one kid was setting the rules for a game; and there were a LOT of rules. So many rules, in fact, that the other kids—initially really excited to play together—started just walking away. What’s true of five-year-olds is true of all of us, whether we’re closer to five or fifty-five; people don’t like working in a system where OMCD takes away their agency.

The pernicious effects of OMCD aren’t just limited to organization staff – OMCD also keeps local leaders from having the space to lead. Empowerment and OMCD are oil and water; they don’t mix. The details depend on what we mean by “local leaders”—but for some of the things folks seem to most often mean with the term we see evidence the tension between OMCD and the negative effects of OMCD.

Where “local leaders” means…

-

Developing country governments: we’ve seen over and over again that as countries become richer, governments start saying “no” to donors. I have some forthcoming research that suggests this is probably a good thing, that more power for donors (and thus less for Governments) in relatively stable, prosperous developing countries may lead to a decline in project performance in those countries.

-

Local NGO or civil society leaders: my work suggests that OMCD focuses attention of donor field agents “up” to HQ and thus precludes the flexibility needed to give these leaders real control. Mark Schuller’s work suggests that OMCD-type funding can undermine local NGOs, co-opting their mission over time even if the funders have the best of intentions.

-

Community members and leaders in conflict environments: Susannah Campbell’s research suggests that peacebuilding projects do better when they empower local stakeholders.

The philanthropy world is increasingly moving away from restrictions on the use of funding. It is high time aid development partners do the same, becoming partners rather than overseers. This requires giving local leaders the space to use their local knowledge and build their organization with support that is actually supportive, rather than seeking to monitor and control. The generalizability of donor’s OMCD should give us every confidence that empowering local leadership is going to be a step forward – including when “forward” is as-judged by development partners themselves.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: DFID/Flickr