Recommended

Rory Stewart, the UK’s new Secretary of State for Development has big ambitions for the country. In light of Stewart’s self-declared candidacy for Prime Minister, we look at four areas where he can demonstrate his credentials and value to UK taxpayers, and bolster international efforts to reduce poverty with UK leadership.

A veteran of development realities

Stewart is not new to development. He served as joint DFID-FCO Minister for Africa, and before politics he helped with transitional governance in Iraq and worked in Afghanistan on reconstruction projects. My colleague Owen Barder has argued that the UK should pursue a whole of government development strategy by using instruments from defense to regulation, alongside aid, to drive development. Stewart’s experience makes him well-placed to lead this agenda.

The UK, and the department he now leads, was once seen as a global leader in driving progress in international development. But there are signs that its leadership is waning. In the past five years, the UK has maintained its commitment to aid spending, but research indicates that the quality of spending has diminished. On the UK’s broader approach to development—for example on environment, technology, and migration—the UK hailed its success in 2015 as the top G7 country in CGD’s Commitment to Development Index, but it has since fallen to mid-table.

The UK remains uniquely placed as a major economy that meets its commitments on aid and defense. Alongside Europe, the UK can play a bigger role as the US steps back and new emerging economies step up. There are four immediate opportunities:

1) Development leadership across Whitehall

Development is about much more than aid, and a Secretary of State with leadership ambitions should lead cabinet colleagues in mobilizing all of government’s tools in support of the Government’s objectives on development. The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) could look at intellectual property rules. In Trade, the UK can improve on the EU’s already-strong trade for development regime. In the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA) and the Home Office, an agricultural workers scheme for workers from developing countries would support industry and development. In Education, the removal of student support for EU students could be replaced with additional support to students from developing countries. In Defense, ensuring arms sales do not undermine our development objectives could be wise. For Transport, mitigating climate change is crucial, for it will affect the poorest the most.

Stewart’s experience in the Foreign Office and the military mean he could be well-placed to bridge these gaps. The Secretary of State is one of just three international voices in a cabinet of 23. He will need to speak up.

2) A higher bar for aid value and effectiveness

The former Secretary of State, Penny Mordaunt, said that aid “must not just ‘be spent well’, but ‘could not be better spent.’” This was a promising start, and the new Secretary of State could energize this challenge to leave a lasting mark on UK aid policy, both in the UK and internationally. Stewart, as someone who has warned against overconfidence about our ability to influence outcomes abroad, is a good person to push this agenda forward.

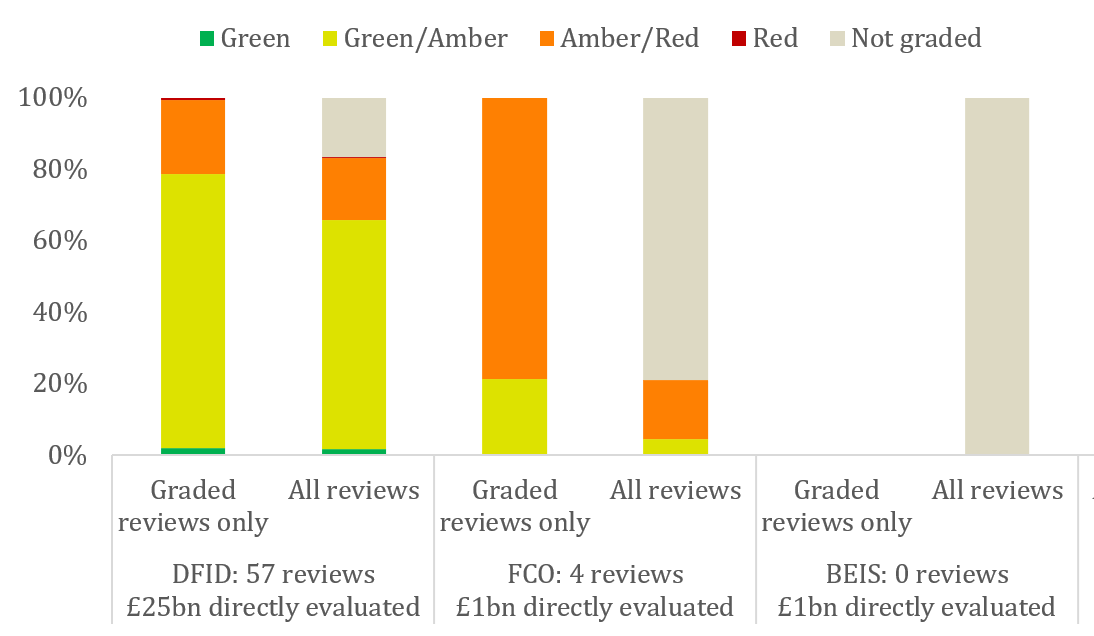

DFID and Her Majesty’s Treasury should make clear that aid will only be spent through departments and agencies with strong performance. Almost 80 percent of aid was well-spent, according to the UK’s aid watchdog the Independent Commission on Aid Impact, but it’s clear that the Foreign and Commonwealth office (FCO) has not performed well. Meanwhile CDC—the UK’s development finance institution slated to receive some £2 billion to 2021—received an amber/ red status for a “lack of clarity on expected development impact.” Funding decisions must reflect evidence in order to maximize development impact and establish good incentives.

A further important step is to set up a What Works Center for development, which would take on a role akin to the role of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in British healthcare. Having an impartial body to compile evidence on what works in development policy would make aid spending more effective, not only in the UK, but also globally.

New leadership is needed globally on aid effectiveness. The “Paris” principles agreed at global summits and updated in 2011 have lost traction, and the world faces new development challenges like those in fragile states. The new Secretary of State could take the lead—starting at the UN’s High-level meetings on progress to the global goals—to refresh and update the global consensus on best practice for aid spending.

3) A new partnership with the EU post-Brexit

The EU and the UK are amongst the largest development actors in the world, and are all the more effective working together. The UK has brought finance and technical expertise while the EU has offered the UK the reach of its extensive presence, access to its financial instruments, and the opportunity to shape its policy, programmes, and direction.

Post-Brexit, the UK and the EU will need to find new ways to collaborate—with joint efforts, joint mobilisation of financial resources, and political efforts that can enhance impact. The Secretary of State will need to enable DFID to invest its resources, time, and thinking to contribute towards and influence EU policy-making on development.

4) Work for a better “multilateralism”

The Secretary of State should stand firm in support of multilateralism by committing resources and making the case at home for working with other countries on challenges like the environment, health, security, and tax.

Multilateral spending is effective. There is a strong theoretical case that multilateral aid could be more effective than bilateral aid; and, according to CGD’s QuODA indicators, the quality of the UK’s multilateral spending is higher than its bilateral spending.

An immediate challenge is for the UK to be strategic about forthcoming “replenishments.” By 2020, donor governments are likely to pledge up to $170 billion to various multilateral organizations as part of their replenishment cycles. Owen Barder and Andrew Rogerson< show how replenishments are currently conducted piecemeal and characterized by path dependency, which has arguably led to a poor-performing multilateral system.

By taking a more coherent approach, more lives can be saved with the same money. A working group chaired by Amanda Glassman outlined a blueprint for donors to systematically implement and evaluate the value for money agenda throughout the grant cycle for the Global Fund and others.

The UK has successfully led reform, and as the largest spender of core aid funding to multilateral institutions, it has a strong mandate for more.

The eyes of the world are on the UK as it navigates Brexit, wondering whether it will turn inward, and whether it will take a step back from development. The new Secretary of State can draw on his experience on the ground to re-establish the UK’s leadership and reinvigorate progress on eradicating poverty.

We’re very grateful for input from Mikaela Gavas, Owen Barder, and Kalipso Chalkidou. All views and any errors remain ours.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Photo by FCO