-

Should we invest in targeted services for particular student needs or just good schools? When students in Boston, Massachusetts who were in special education or in “English language learner” programs enrolled in high-performing charter schools—which included “high intensity tutoring, data driven instruction, and increased instructional time”—they often lost their special status (and the access to services that the status brings). Despite that loss, enrollment in charters led to large achievement gains, including college enrollment. As economist Elizabeth Setren shows, entrance into the charter schools was assigned by lottery, so the improvements aren’t explained by who gets into a charter school (but it is limited to those who apply to charter schools, of which there are many special needs students).

This doesn’t mean we toss out specialized programs: obviously certain special needs require special services. But it does mean that investing in all-around high-performing schools may in some cases be more effective than certain specialized, targeted programs. This parallels my own recent work with Fei Yuan, which shows that general investments in improving education can sometimes do just as much for girls’ education as targeted programs. Specialized programs don’t necessarily compensate for good schools.

-

Is student learning improving around the world? It’s really hard to know, since “most countries are still unable to tell by looking at their national assessment data whether learning levels are improving or declining over time,” according to education researcher Marguerite Clarke. She highlights two ways that countries can improve testing to gauge trends over time. One is to embed a subset of questions that appear in each version of the test; another is to have the same set of students take multiple versions of the test.

-

More content knowledge may not be enough. Several recent studies have highlighted that teachers in low- and middle-income environments may lack mastery of the content they are supposed to be teaching. It’s hard to imagine an effective geometry teacher who doesn’t know geometry. One study suggests that across seven African countries, differences in teacher content knowledge may explain 20 percent of the differences in student learning.

But increasing content knowledge alone may not be enough. In a recently published study, Lu and others found that in China, a teacher professional development program to increase math content knowledge succeeded in boosting teachers’ math content knowledge (yay!) but had no impact on students’ math achievement (boo!). Teaching practices also didn’t change, and the program had no follow-up in the classroom. So yes, increase teacher knowledge, but then help them implement it.

-

The purposes of economics in education research. Economist Karthik Muralidharan—who you might know for his research hits on teacher performance incentives, education technology, and bicycles for secondary school girls, among many others—gave an interview on how he became an education-focused economist. Here’s one reminder on how economics is a tool, not an end: “One of the best pieces of advice I got from my advisor, Michael Kremer, was ‘Never apologize for the fact that your fundamental motivation is to make sure 200 million kids in India have a better education and that economics is a tool to get you there… It’s a very powerful tool, but it’s not an end in itself.”

Here’s one more excerpt, on what economists bring to the education table: there are “always more things to do than you have money for, and then the question is, how do you decide? If you line up 20 experts in education, often you will get 20 different opinions, and none of these are individually wrong, but unless you have research and evidence on how you actually figure out cost-effectiveness of different things, you just don’t know what to prioritize. One of the most important things for me over the past 20 years has been seeing how there is just stunning variation in the cost-effectiveness of policies that sound equally sensible sitting in a conference room. So the job of the researcher is to bring objective evidence into this thing.” Economists aren’t the only ones who measure cost-effectiveness, but we may have a comparative advantage in it. (I’ve very lightly edited Muralidharan’s quotes in the transition from a verbal interview to a written blog post.)

-

If you treat a Zambian child’s parents for HIV, the child is more likely to start school on time. As if there weren’t enough reasons to treat an HIV-positive person (Lucas, Chidothe, and Wilson).

-

What about education for the adults? In Germany, work-related training not only yields financial gains but also “increases participation in civic, political, and cultural activities” (Ruhose, Thomsen, and Weilage).

In case you missed it here on the CGD blog, Rossiter and Ishaku call for more and better research on education in Africa, rounding up the results of a recent conference on that topic. Woldehanna, the president of Addis Ababa University, offered another take on the same conference over at the RISE blog.

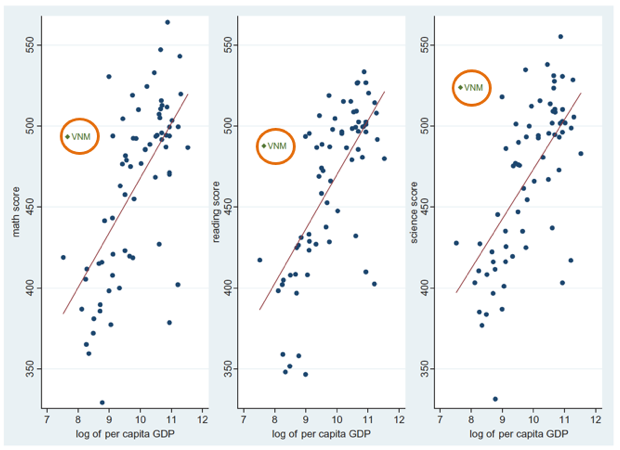

Chart of the week: Vietnam performs extraordinarily well in student exams, given its level of income. Over at the RISE blog, Jonathan London explores what’s going well, why, and where Vietnam still struggles.

Source: London (2019), minorly adapted from Dang and Glewwe (2018).

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.