Recommended

Just about every school district in the world has schools that it struggles to staff. Many teachers don’t want to work in remote schools, or they don’t want to work in urban schools with high concentrations of poverty. Teachers play an obvious, crucial role in the education process, so how can systems get teachers—especially effective teachers—into disadvantaged schools? In our new paper—“How to Recruit Teachers for Hard-to-Staff Schools: A Systematic Review of Evidence from Low- and Middle-Income Countries”—we explore just that.

What tools can systems use to draw teachers to hard-to-staff schools?

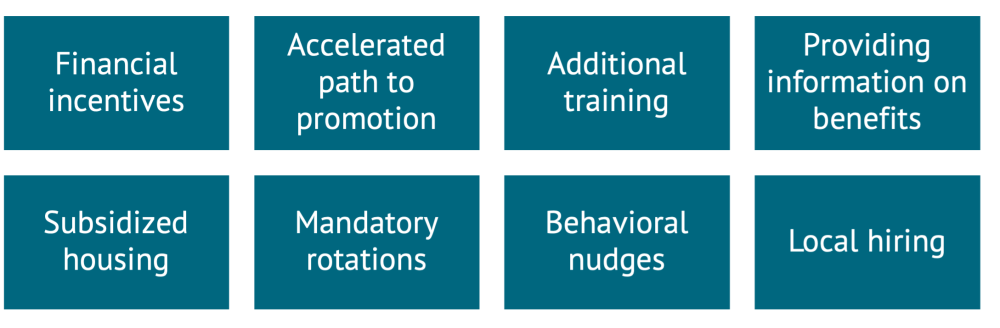

Education systems around the world draw on a wide range of policies and programs to attract teachers to hard-to-staff schools (Table). They offer financial incentives and accelerated paths to promotion; they implement mandatory rotations to rural or otherwise disadvantaged schools. They list disadvantaged schools first on lists for teaching candidates (as a behavioral nudge), and they provide information about the benefits of teaching in these schools. But how well do these programs work?

Table. Menu of policies to attract and retain teachers in hard-to-staff schools

We combed through thousands of studies to identify those that evaluate the impact of policies or programs to bring teachers to hard-to-staff schools. Ultimately, 15 studies provided quantitative measures of the impact of the programs on teachers or students. Another six studies, while not evaluating programs, described them and provided qualitative evidence of teacher or administrator experiences with the programs. Three more studies tried to understand what it would take for teachers to relocate to hard-to-staff schools by posing hypothetical scenarios (e.g., would you rather teach in the city for a certain monthly salary or teach in a remote school for 50 percent more?). Of the 15 quantitative studies, 12 examined financial incentives to teachers. (This high concentration of financial incentive evaluations is consistent with research in high-income countries as well.) The other three evaluations examined behavioral nudges, providing information on benefits in teaching in disadvantaged schools, and a national recruitment drive. All of the studies we learn from (the quantitative as well as the qualitative studies) come from programs in Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa and Asia (Figure).

Figure. Where we learn about policies to recruit teachers to hard-to-staff schools

Note: A few countries have multiple kinds of studies—e.g., Peru has both a financial incentive evaluation and a behavioral nudge evaluation. For full details, see Table 1 and Table A1 in Evans and Mendez Acosta (2021).

How effective are financial incentives?

There’s good news and there’s bad news. The good news is that most programs that offer financial incentives to teachers increase teacher placement or reduce turnover in hard-to-staff schools. From Peru and Uruguay to Zambia and the Gambia, offering teachers more pay—often between 20 and 30 percent more—works. Just one program—in Chile—explicitly sought to increase the supply of highly qualified teachers in hard-to-staff schools. Giving teachers who received a “teaching excellence bonus” an additional premium if they taught in hard-to-staff schools decreased turnover in those schools.

Studies that report student outcomes mostly find positive impacts as well. But while almost every study reported teacher outcomes, only 9 of the 15 reported student outcomes, so we can’t be sure what would have happened in the settings where student outcomes went unreported. But student test scores rose in Peru, student attendance improved in Uruguay, and test scores rose for subsets of students in the Gambia (richer students) and Zambia (boys).

The bad news is twofold. First, one study in Peru showed that financial incentives drew teachers to disadvantaged schools (great!), but many of those teachers were transferring from schools that were only slightly less disadvantaged (not so great!). This means that some of the positive effects we observe in other studies might be overstated. At least one study—in the Gambia—provides evidence that this isn’t driving their results (phew!). The other bad news is that while financial incentives do boost the number of teachers in hard-to-staff schools, they don’t close the gap with other, more advantaged schools. Another study in Peru finds that it would take about twice the current total national budget for teacher salaries to fill every vacancy in rural schools, and that it would take up to six times the salary budget to close the quality gap between rural and nonrural schools.

Can we get more female teachers in hard-to-staff schools?

The presence of female teachers may have positive impacts on both girls’ learning and girls’ aspirations, especially in secondary school. But getting female teachers to remote schools or high-poverty areas can be extremely challenging. Women may have greater security concerns or greater expectations that they’ll follow a spouse rather than the other way around. In India, female teachers reported that they would need a financial incentive of between 24 and 73 percent more than their existing salary to move to remote schools, higher than many existing programs. This checks out in at least one program: in the Gambia, a salary bonus of between 30 and 40 percent did boost the number of female teachers in rural schools.

What else works?

Beyond financial incentives, what else works to draw teachers to hard-to-staff schools? In Ecuador, teaching candidates select the schools where they’re willing to teach from a list. The government tried a simple nudge: it moved the most vulnerable schools to the top of the list! Candidates who saw the list with vulnerable schools at the top were 3 percentage points more likely to take a job at a hard-to-staff school. In Peru (yes, another Peru study), sending teachers messages to remind them of the impressive impact they can have on students in vulnerable schools boosted teacher placement in those schools, although only for male teachers.

Lots of countries draw on contract teachers to fill vacancies: the profile of these contract teachers can range from local individuals who received teacher training but didn’t find a position to literate community members who received just a little bit of training before entering the classroom. The impacts of these programs have mostly been evaluated in the context of non-state interventions (e.g., in India and Kenya) and have shown positive impacts, although evidence is limited from government-implemented programs. At least one study showed that government implementation—in Kenya—brought a loss of effectiveness.

Other programs—such as providing an accelerated path to promotion, subsidized housing and mandatory rotations—simply lack quantitative evidence of impact. Qualitative studies suggest that, like all programs, they face challenges. For example, China has a mandatory rotation program, where urban teachers go to short-staffed rural schools for one to three years. In interviews, rural school principals highlighted that these teachers often showed up late or refused to teach on Fridays, and the principals lacked authority to hold them accountable. In Malawi, urban teachers said that providing housing would make them more likely to move to hard-to-staff schools, whereas rural teachers reported that housing didn’t provide them much of an incentive to remain. The researchers posited that perhaps the reason was because the rural teachers had experienced the poor quality of the provided housing firsthand. This doesn’t mean these programs can’t work, just that we need better evaluations of them and that the devil is often in the details of implementation.

Takeaways

Education systems can draw on a wide array of policy options to attract teachers to rural or otherwise vulnerable schools. Financial incentive programs tend to narrow the gap between the number of teachers in hard-to-staff schools and other schools, even if they don’t close it entirely. Behavioral nudges and informational interventions are low-cost ways to get at least some teachers into vulnerable schools. There are examples of other policies in many other countries that education systems can draw on and—importantly—test to see if they achieve what they intend: effective teachers for all students!

Want to find out more?

We can’t put everything in a blog post, so here’s a quick rundown of questions we seek to answer in the paper that we didn’t cover above: How bad is the problem of staffing in hard-to-staff schools? Read section 3.1.1 in the paper! Are absenteeism and teacher competency lower in hard-to-staff schools? Read section 3.1.2! What is the range of amounts that financial incentive programs offer across countries? Read section 4.1! How hard is it to implement financial incentive programs effectively? Read section 4.2! Want to read more on this topic? Find more studies in section 1!

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Aisha Faquir/World Bank