News that France is legislating a target to give 0.7 percent of GNI as official development assistance (ODA) inspires mixed feelings in me. I have always been ambivalent about this target for wealthy nations, and not necessarily because it’s based on an arbitrary and outdated calculation (though it is). In fact, in spite of its genesis, the number seems, if anything, on the low side: most recipients could absorb substantially more aid than they get, provided it is given well. Nor is my concern that we’re running out of good things to do in developing countries—a cursory glance at GiveWell suggests multiple development objectives that have a great deal of string left to play out (and even if ODA should do different things to private philanthropy, the case that there are many things it can do effectively and which need more funding has never been easier to make).

My concern is more akin to Goodhart’s law: when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure (though coined in this formulation by Marilyn Strathern). When an aspiration to meet a specific level of funding drives new aid spending, rather than a political settlement and institutional structure that prizes development outcomes and allocates funding for good work to that end, we cease to give due attention to that all-important clause: “provided it is given well.”

This does not mean more aid isn’t a good thing. Nor does it mean that cuts during a global pandemic—as the UK is implementing— are not a terrible idea. Both statements are true. And arguing that introducing a target to reach 0.7 percent of GNI is a bad idea may give cover for bad actors who don’t care about development and want to avoid our obligations to the rest of the world. But introducing a target can give cover to other kinds of bad practices and bad actors, with long-term negative consequences for development. It’s great that France wants to give more aid, but a target is a bad way to do it.

In this blog, I set out three channels through which the adoption of the 0.7 percent target can have negative consequences, illustrating them with the example of the UK experience, and how France can be more generous while avoiding these pitfalls. Spoiler: a target isn’t the answer.

Three possible perverse effects of adopting 0.7

The key insight of Goodhart’s law is there is a difference between making progress on a measure incidentally and in targeting it for its own sake. A number of countries give more than 0.7 percent of GNI in ODA as a result of political settlement and policies that value better international development outcomes, and a resource allocation process that reflects this. As my colleagues have shown, these countries tend to give good aid—and they give a lot, because they value using aid well. When 0.7 is the result of striving for 0.7 itself rather than the consequence of valuing development highly, three distortive effects may arise.

- Buy a hammer and everyone shows up with nails. All arms of government are short of money in most countries. Creating a protected budget attracts other arms of government appropriating some portion of the uplift to 0.7 for things that ODA shouldn’t do, even if they fit under the rules —a number of which I proposed axing in the context of the UK aid cuts here. These bad actors won’t capture the full uplift, so moving to 0.7 still does some net good—while it lasts.

- Intra-marginal spending doesn’t change. The target itself does nothing to change the quality of the ODA that was already done before it is adopted—which may be good or bad news, depending on how well it was used before the uplift.

- A shift in the political economy of aid allocation. This is the key problem, and an extension of Effect 1. When the budget is protected and other arms of government capture part of it for security, migration, or prosperity objectives for which aid is poorly suited and which have few real development payoffs, this creates a fundamentally new political economy of aid within the government. Should the budget fall again—as in the UK—this new political economy means we don’t simply go back to where we started, because these new players have greater clout. The cuts will be disproportionately focused on the best development spending.

These effects mean that in the short run, more good is done in total by adopting the target, even if the average quality of the new spending is worse than what came before. It is the third effect above that is so poisonous to development prospects in the long term. If generous aid spending isn’t a political equilibrium without legislative protection, it’s unlikely to be one with it. Scaling up and scaling down aid will therefore be asymmetric.

The UK experience as a cautionary tale

I had a front row seat to the UK’s adoption of the 0.7 percent target. My very first job in what was then DFID was in the team that provided advice on proposed legislation to enshrine the target in law (the target was already being discussed in Parliament as early as 2010). The government position then was that it would introduce legislation when Parliamentary time allowed, given the other bills vying for attention. In the meantime, with a secretary of state, prime minister, and chancellor who all believed in development spending, the UK was ramping up its aid spending over time in any case. Only one serious attempt was made to put the legislation before Parliament—very low down the list of government bills that day so it was clear it was unlikely to pass, as indeed was the case. (In the end it wasn’t even debated.) Nevertheless, after final estimates came through, the UK had in any case given 0.7 percent of GNI as ODA in 2013.

The very next year Michael Moore, a Liberal Democrat MP, introduced a Private Member’s Bill (PMB) to enshrine the 0.7 percent target in law—and this time the government supported the bill, signaling early on that it would likely find Parliamentary time (as PMBs have a separate chunk of Parliamentary time allocated to them) and would pass into law (because the coalition government had a majority). The law became official in 2015. Though it gave aid protection during a period of austerity, the aid budget immediately became a target for departments that had never previously shown any inclination to international development work. The trajectory of UK aid since that point is a warning.

Figure 1 . ODA as a share of GNI and UK aid spending by department

>Source: Statistics on International Development 2019, author’s analysis

Each mechanism by which Goodhart’s law can undermine the 0.7 target has been realized. When the law had little chance of passage (2010-13), there was virtually no change in the proportion of ODA being secured by non-development-focused arms of government. In 2014, once the PMB was introduced and sponsored by the government, we see a jump in the ODA administered by non-development parts of the UK government, gathering pace after the legislation passed in 2015. The grab of ODA by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy; the Home Office; the Foreign and Commonwealth Office; and others was not a product of the change in the political landscape in mid-2016 after the Brexit vote, but had already largely been accomplished by then.

Meanwhile, it is clear that the intra-marginal effect of 0.7 was limited: the bulk of DFID’s work was much better in development terms than its sister departments, as made clear by independent evaluation, and very little previously existing work was halted. Effect 2, that 0.7 does nothing in and of itself to change what came before it, was a positive, since the legacy portfolio was strong.

The final, and most poisonous effect of the cuts was the shift in the political economy of aid in the UK. Figure 1 clearly demonstrates that other government departments began using aid much more. But what the numbers don’t show is the way the terms of this engagement changed. There was a common sense in DFID that initiatives in other departments like the Prosperity Fund were poorly managed and less good for development. Nevertheless, they were considered a “necessary evil” of having a protected budget. Indeed, DFID staff were seconded to other government departments to help them manage their aid better. This reflected the imbalance in both effectiveness and power across government. As if to hammer this point home, in November 2015—much to the surprise of most of DFID—a new aid strategy was published, relegating poverty reduction to one of four targets of UK aid, rather than its overarching focus. Again, this did not a reflect a rightward shift in the government. The Cabinet was materially similar to the pre-0.7 Cabinet, and the EU referendum was in the future. What changed were the returns to encroaching on development, given that the protected budget near-guaranteed the pot that could be fought over. When the cuts came this year, the development teams fought extremely hard to protect their spending. But there is little doubt that what remains will be weaker than what came before, and less focused on doing good development work.

What about France?

France should learn from the UK experience. Even though the new legislation commits only to “strive” towards 0.7, we can expect that with an upward pressure on development budgets, there will be pressure from arms of government without a protected budget to make use of it. The first and third negative effects of treating 0.7 as a target itself, rather than the outcome of resource allocation processes that value development appropriately, are a danger. The direction of the second effect is less clear, and this suggests the bones of an alternative approach that can improve the generosity and quality of ODA without the negative effects.

French aid, as it stands, is poorly targeted. It does not focus on either poor people or poor countries. The second “effect” of 0.7 legislation, that it does little in and of itself, to improve the existing ODA given is a negative in the French context.

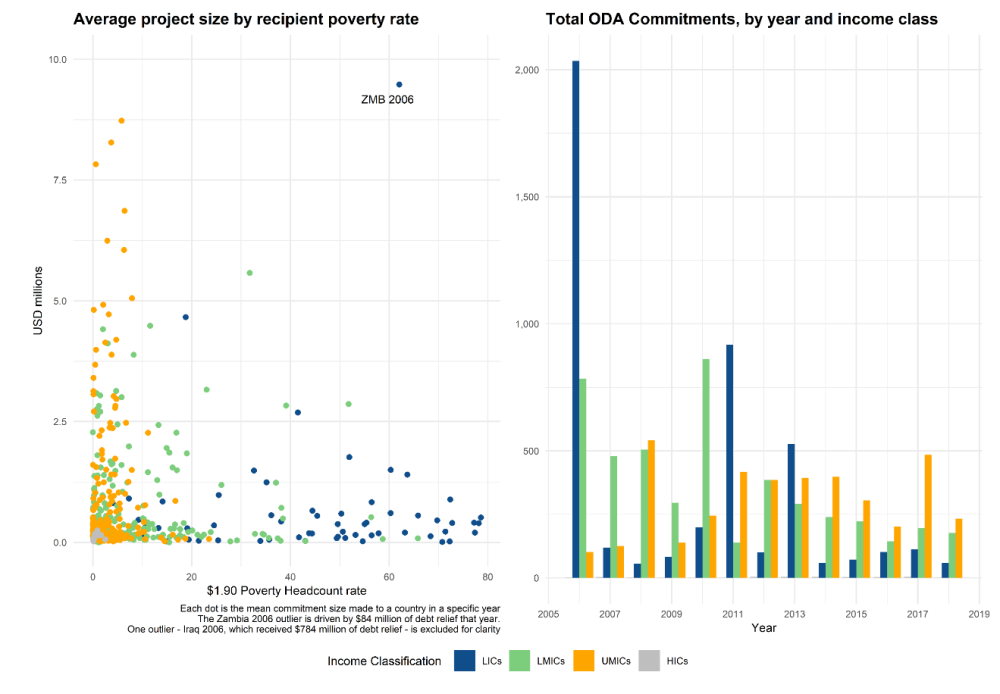

Figure 2. French ODA is not well targeted at poor people or poor countries

Source: OECD CRS data 2006-2019

To their great credit, French lawmakers recognize this, and have used the law to legislate a better use of ODA across the portfolio: more focused on poorer and more fragile countries, and assessed for quality by an independent body. They may be able to partially occupy the space abdicated by the UK in international development, especially with elevated needs post-Covid. Coupled with the new Development Innovation Fund chaired by Esther Duflo there is much to cheer in France’s trajectory. These changes suggest an alternative approach to doing development better than legislating for how much you spend.

A better way

A better approach has three arms.

- Legislate for outcomes, not inputs. One of the reasons DFID was an effective organization was that it was bound by legislation that made poverty reduction the legal mandate of its work. Regardless of what it spent, it would need to be justified on poverty reduction grounds. The great weakness of the legislation was that this requirement wasn’t biting enough, and didn’t establish a burden of proof or define poverty reduction. Making development objectives an immutable part of the organizational mission focuses the organization and helps recruit mission-oriented people.

- Commit to robust scrutiny. DFID was also one of the most externally scrutinized arms of the UK Government, with a Parliamentary Committee (the IDC), the Independent Commission on Aid Impact, and the National Audit Office all taking aim at it. Alongside this, it made robust commitments to transparency of spending and procurement. There are few skeletons in the closet because there are few closets.

- Get the internal processes right. DFID’s effectiveness was built on the pillars of technical expertise—a strong cadre of economists, political scientists, anthropologists and more—and intense contestability. DFID prioritized its own ability to generate, commission and interpret research. Technical experts were constantly making the case for spending on alternative objectives based on evidence and assessing the case made by others. But this wasn’t a free-for-all: a system of evidence-based spending cases (business cases), annual reviews, and internal quality assurance kept them honest.

This approach does not guarantee that good development work takes up an increasing portion of what the government does. But neither does a 0.7 percent target, especially if it has perverse effects when abandoned. More money can mean more welfare gains, but only if it’s spent well. The effort and political capital it takes to scale up spending may be better used to make existing aid better: targeting it at countries and people who need it more, using it to achieve things that other means cannot do more efficiently, resisting the urge to try and make it do things it simply cannot achieve or to use it as an (inefficient) means of self-enrichment. When these are the battles that should be fought, shifting the terms of the debate to the overall budget is not an effective strategy for improving global welfare.

0.7 is a convenient campaigning topic. But Daniel Kahneman famously observed that when faced with a difficult question, we often substitute it for an easy question—and do not notice the substitution. The difficult question is “how do we do development well, and at scale?” The easy question is “how much money in the budget can we secure?”

The difference matters. We should ask the difficult question.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.