Recommended

Gross domestic product (GDP) is one of the most widely used measures of a countries’ economic performance. GDP per person is used to measure standards of living, the debt to GDP ratio is commonly used to assess debt sustainability, and it has a bearing on voting power at many multilateral institutions. Many aid allocation models include GDP per capita as a key variable.

However, measuring GDP is resource intensive, and as a result it is systematically measured more accurately in richer countries. This does not just mean that there is more uncertainty in GDP numbers for lower-income countries: it means that GDP could be being understated in developing countries.

This blog explores the extent to which countries use out of date information to estimate GDP and finds that low-income country (LICs) GDP could be a third higher than currently believed, and that lower middle-income country (LMICs) GDP could be over a quarter higher. In total, this would mean that 7 percent of the global economy is being missed. The implications of this are broad, and simply investing in better data could very well pay for itself.

The importance of the “base year”

The 2010s saw a number of high-profile adjustments to GDP among African countries. Nigeria, Ghana and Kenya respectively increased their GDP by 90 percent, 60 percent and 25 percent. These adjustments made a big difference to what we thought we knew about the continent—Nigeria became Africa’s largest economy—and highlighted just how problematic GDP figures can be.

These adjustments are a result of updating the “base year” by which GDP is measured. When measuring changes to GDP between years, national accountants use a base year for which there is especially good data. Changes to different sectors are calculated relative to this base year, and to obtain growth in real terms, output is measured at the prices prevailing in that year (this applies to all sectors but is easier said than done for services). The base year is usually chosen to coincide with a business census that attempts to capture all economic activity in the economy. The GDP in subsequent years is then calculated using smaller surveys that measure how much each activity has grown.

Richer countries can afford to collect data on (nearly) all businesses every year, and so update the base year each year (chain-linking the measure of GDP). Given how expensive this is, it is generally not possible for developing countries, so base year changes are less frequent. The System of National Accounts (who offer international guidelines on measuring GDP) recommend updating the base year at least every five years. Even this is not possible for many developing countries. The table below shows how long ago the base year currently in use is for all countries that do not “chain-link” their GDP measurement.

Table 1: National accounts base year by country

| Country | National Accounts Base Year |

|---|---|

| Barbados | 1974 |

| Madagascar | 1984 |

| Haiti | 1987 |

| Yemen | 1990 |

| Republic of Congo | 1990 |

| Bolivia | 1990 |

| Liberia | 1992 |

| Sudan | 1996 |

| Venezuela | 1997 |

| Mali | 1999 |

| Burkina Faso | 1999 |

| Syria | 2000 |

| Philippines | 2000 |

| Honduras | 2000 |

| Eritrea | 2000 |

| Cambodia | 2000 |

| Bhutan | 2000 |

| Belize | 2000 |

| Nepal | 2001 |

| Gabon | 2001 |

| Thailand | 2002 |

| Angola | 2002 |

| Libya | 2003 |

Source: World Bank

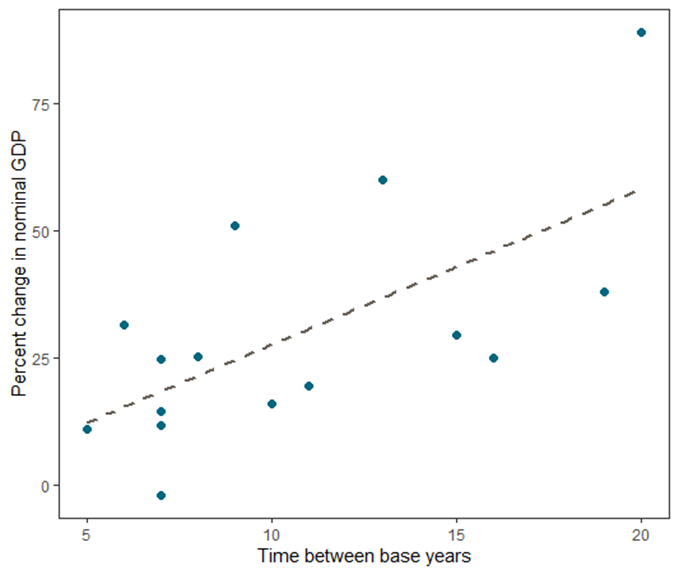

The impact of the delay in updating base years is not completely random. There is a clear positive relationship between the length of time between different base years, and the resulting increase in the size of measured GDP. This makes intuitive sense: economies change over time, and new activities arise. The more time between base year changes, the more new activities are missing from GDP figures. In Nigeria’s case, the base year was updated from 1990 to 2010. In between these dates, Nollywood became the second largest producer of films in the world, mobile phones became ubiquitous, and the retail sector exploded. Essentially none of this activity was captured in the GDP numbers. Figure 2 plots length between base year changes and the resulting change in GDP. Although only a handful of countries are included (found via an internet search) the relationship is clear. Only one country recorded a (slight) decline in its GDP post-rebasing.

What does this mean for GDP numbers?

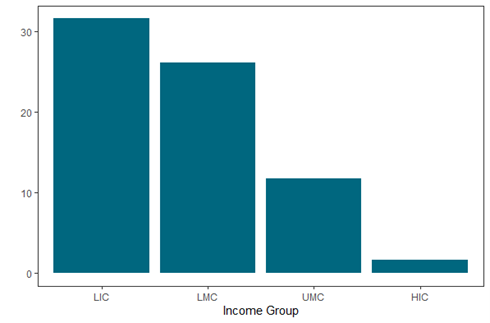

This blog takes this relationship seriously. If we apply it to the countries that currently have an out-of-date base year (defined as any country with a base year older than 2019) what impact would this have on countries’ share of global GDP? Below, we estimate the increase in GDP that would occur if countries update their base year and this relationship holds across countries. It implies that for every year since the base year was updated, GDP is three percent higher than official figures suggest.Figure 2 demonstrates this change by income group. As expected, LICs see the biggest change: if the above relationship holds, LICs’ GDP is 32 percent higher than official data suggests. The GDP of LMICs would increase by around 26 percent. Globally, these estimates suggest that world GDP is around 7 percent higher.

Figure 2: Estimated percent change to GDP if base years are updated, by income group

Notes: World Bank income groups are used. GDP measured in current USD

Source: World Bank Data

While care should be taken in applying this simple relationship to individual countries, it could also have implications for the number of LICs. Liberia, Burkina Faso, and Mali have not updated their GDP base year in over 20 years, and the above relationship applies to them, each would cross the middle-income threshold. Even Madagascar would cross the middle-income threshold: the fact that it is officially one of the poorest countries in the world might be in part because it hasn’t updated its base year since 1984. Several more countries would cross the upper-middle income threshold, such as Morocco, the Philippines and Bhutan. This means they would no longer be automatically eligible for financing from the Global Fund, suggesting an arbitrariness to using GDP per capita thresholds when measurement varies so dramatically across countries.

Could better data pay for itself?

These estimates are overly simple, and given that the data points were found via internet searches, there be some selection bias (with bigger changes being more newsworthy). But if they are close to the truth, it would change what we know about the global economy, about which countries are the poorest, and about how aid should be allocated.

This issue is not new: last year, my colleague Ranil’s new year wish was that countries would invest more in the quality of data, but understandably, revising national accounts was not the top priority in a year in which many were still dying from COVID-19 and new variants were emerging.

Yet, there are benefits to improving data. World Bank

It matters for ODA providers too, and there have long been calls for more assistance with developing national statistical systems. Investing in statistical capacity is not sexy, and will not feature on the front pages of donor impact reports. But given that aid allocation is highly dependent on GDP per capita (or the closely related GNI per capita), aid providers clearly have an interest in ensuring that data remains up to date and relevant. Given the importance of data and information for forming policies, both developing country and provider governments have strong reasons to do better on measuring GDP.

This blog benefitted from excellent comments from Ian Mitchell, Ranil Dissanayake, Rachael Calleja and Charles Kenny. Any errors remain the author's own.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.