The authors are grateful to Beata Cichocka for her input and representation of the data.

Last week, the European Commission’s President Ursula von der Leyen unveiled her new proposal (Next Generation EU) for a post-COVID-19 economic Recovery Fund, alongside the EU’s future priorities and budget, the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) for 2021-2027. In total the proposal is worth a colossal €1.85 trillion. This is, undoubtedly, a make-or-break moment for the future of the EU project. European leaders have, to date, been unable to come to an agreement on the EU’s long-term budget. With less than six months to go before the expiry of the current MFF, and with a continent ravaged by a pandemic, time and action are now of the essence. But what do the proposals mean for Europe’s role on the international stage? Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, we saw major tensions at the heart of the EU project. If Europe cannot credibly come together internally and project its influence externally, its centrifugal forces will only strengthen, and it will lose relevance and legitimacy, perhaps sliding into terminal decline. In this blog we outline the details of the Recovery Fund and examine the provisions for international development funding.

Of the newly announced €750 billion Recovery Fund, €15.5 billion would be allocated to the EU’s international development. While there has been a precedent of EU international development suffering disproportionately from cuts in the EU budget, the Commission’s proposed boost is a welcome recognition that failure to respond and to invest in international reconstruction will create a devastating long-term political and economic crisis that will directly impact Europe. But does this budget truly reflect the EU’s geopolitical and cooperation ambitions (as detailed in von der Leyen’s plan), in particular with Africa—which von der Leyen referred to as “our close neighbour and our most natural partner”?

What’s changed since the last iteration of the MFF?

Negotiations have relaunched on the EU’s MFF, its seven-year budget that will come into force in 2021. The MFF sets the EU’s strategy, priorities architecture and finances for a seven-year period. Plagued by member state wrangling and horse trading, the MFF proposal originally launched by the European Commission in 2018 and subsequently revised by European Council, had hit an impasse before COVID-19 broke out. The new proposal published by the European Commission last week entails an ever-so-slight increase on the proposals put forward by Charles Michel, the European Council President in February 2020, from €1.09 trillion to €1.1 trillion, albeit a decrease from the original proposal put forward by the European Commission in May 2018 (€1.13 trillion). It is the additional proposed recovery fund of €750 billion—to provide immediate and temporary support for the regions and sectors hardest hit by COVID-19—which is the game-changer (€500 billion in grants and €250 billion available as loans). This is additional to the €540 billion support package for workers, business, and member states the EU had agreed on in April 2020.

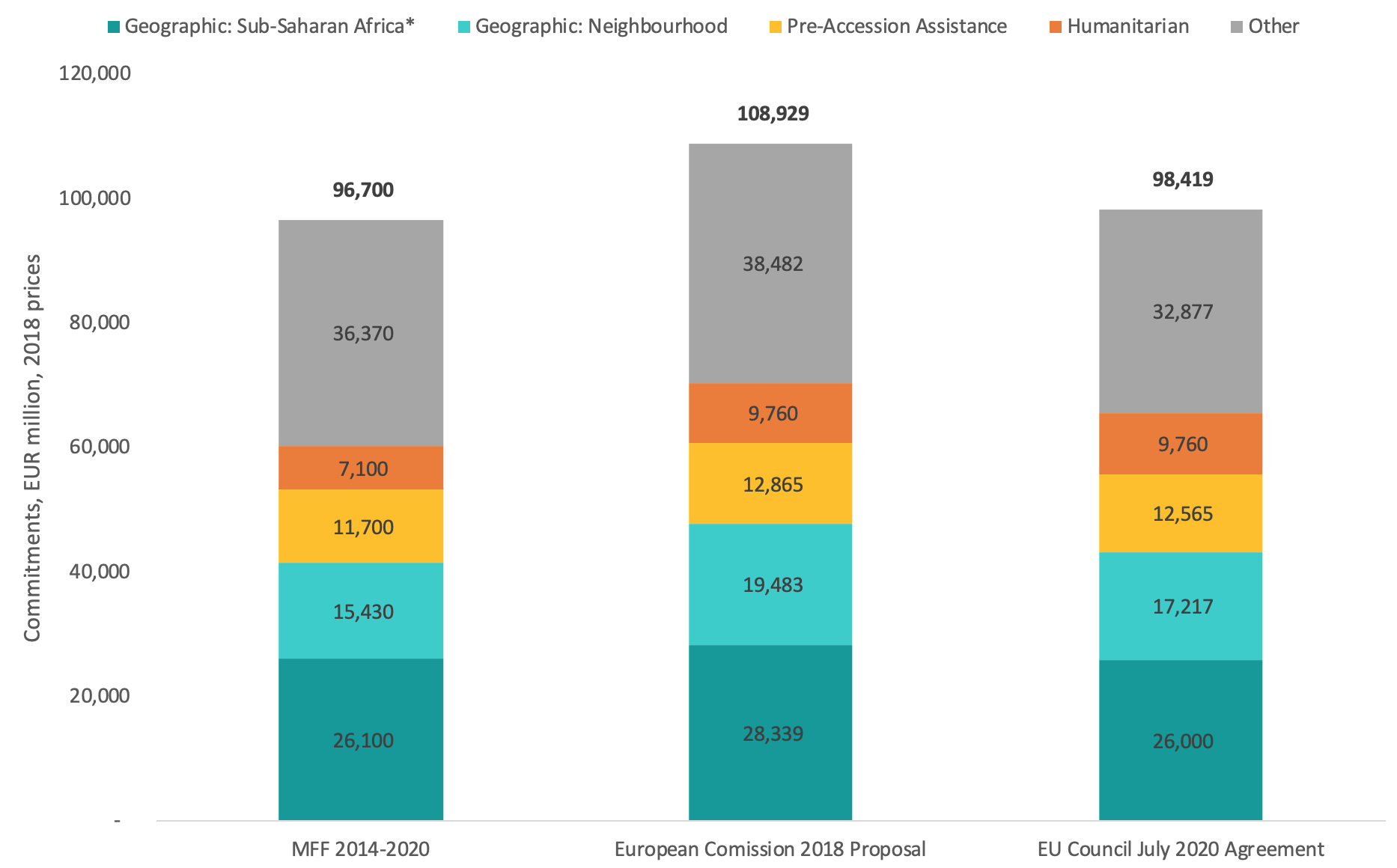

Figure 1. Evolution of MFF Proposals

Source: Commission's 2020 Proposal, President of the European Council's Proposal, Commission's 2018 Proposal

There is a lot of emphasis on spending the common resources on areas that align with the EU’s future-looking priorities, including boosting competitiveness, shifting away from declining heavy industry, supporting the EU’s green agenda and building the digital economy. Unsurprisingly, cohesion programmes get the bulk of the recovery fund (€610 billion of the €750 billion total) to support some of the hardest-hit member states.

Figure 2. Distribution of the MFF and Recovery Fund across spending areas (Headings)

Source:https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/about_the_european_commission/eu_budget/1_en_act_part1_v9.pdf

How does international development fare?

While COVID-19 has brought with it a whole raft of new challenges, these have been overlaid on older global and regional threats including climate change, fragility and conflict, and refugee crises with increasingly frequent and serious flashpoints.

There is no doubt that the global crisis and economic recession following the pandemic will hit developing countries disproportionately hard. The EU is still very much in firefighting mode—ploughing money into COVID-19 R&D; providing budget support and cash transfers to developing countries; providing access to loans and guarantees; re-orientating investments across portfolios to focus on responses to COVID-19. In April, it had already mobilised almost €19 billion for a global emergency response, support for healthcare systems and economy recovery which will likely help shape its longer-term engagement with some of the more vulnerable people and countries in Africa. Of course, none of this was additional money, but rather frontloaded from existing programmes. There are limited funding options at this stage, with the 2014-2020 budget period coming to an end.

The proposal provides little detail on international development, apart from overall figures. What we do know is that the Commission has proposed an increase to Heading 6 (Neighbourhood and the World) from €108.9 billion to €118.2 billion, with the “core” of the proposal largely unchanged from the Council’s proposal. Rather, the new money comes from the Recovery Fund. Of the €15.5 billion top-up from the Recovery Fund, €10.5 billion will be allocated to the Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument (NDICI) via the External Action Guarantee (the EU’s risk-sharing tools for investment in developing countries). The design of the NDICI will, in all likelihood, remain similar to the one proposed in 2018. This streamlined the instruments and introduced a fair amount of flexibility in spending, in spite of member state wranglings over the integration of neighbourhood and developing country spending. The remaining €5 billion of the Recovery Fund is put aside for humanitarian aid, which represents a whopping 50 percent increase on both of the previous proposals, and more than double the existing humanitarian budget (€ 7.1 billion in the last MFF).

Figure 3. External Action Financing Instruments under Heading 6 of the MFF proposal

Source:https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/about_the_european_commission/eu_budget/1_en_act_part1_v9.pdf

In addition, as part of Heading 5 (Resilience, Security and Defence) the proposal allocates €2 billion from the recovery fund to rescEU, the Union's Civil Protection Mechanism which will be expanded and strengthened to equip the EU to prepare for and respond to future crises.

Migration

Nevertheless, the new proposal seems to put the refugee crisis on the backburner despite the constant stream of refugees to Europe’s shores during the pandemic. Heading 4, Migration and Border Management, mirrors the 2018 proposition, with a minor increase from €30.8 billion to €31.1 billion. Von der Leyen’s predecessor’s 2018 proposal was a direct, albeit reactive response to the surge in refugees to the EU in 2015, with a major focus on border control and enforcement. The new proposal allocates an additional €1 billion to the Asylum and Migration Fund (AMF), a successor of the current Asylum, Integration and Migration Fund. A major criticism of the AMF is the absence of the integration objective, as member states would not be obliged to allocate any of their share of the AMF to integration, including the establishment of legal migration mechanisms. While funding for the integration of migrants would be part of the European Social Fund, which sees a proposed decrease from €89.7 billion to €86.3 billion, use of these funds on measures for third country nationals is at the discretion of member states.

Peacebuilding

Surprisingly, the European Peace Facility (EPF), a major initiative to finance operations and Actions in Africa, is notable for its absence in last week’s proposals. The EPF, worth €10.5 billion in total, was originally proposed as an off-budget fund by former High Representative Mogherini to support operations such as the G5 Sahel Joint Force. In President Michel’s February 2020 proposal, the facility was cut down to €4.5 billion for the period 2021-2027. It remains to be seen if and how von der Leyen remains committed to her geopolitical ambition by boosting the EPF and supporting peace operations in Africa and beyond and investing in capacity building of partner countries’ armed forces.

The environment

The new proposal attempts to reinforce von der Leyen’s ambition to transform Europe into the first climate-neutral continent and use the opportunity of COVID to “build back better”—at least in numbers. The “Just Transition Fund” (JTF) sees a significant increase in the new proposal. The JTF, originally at €7.5 billion was first proposed in January 2020 as part of the European Green Deal initiative and aims to support transition towards climate neutrality. In practice, the JTF aims to provide grants to finance social support, economic revitalisation, and land restoration for regions struggling with the green transformation. Last week’s proposal would see an increase from €32.5 billion to a total of €40 billion. The main recipients of the money would be Central and Eastern European countries, to support them in their move from fossil fuels, mainly coal, to green energy. But the proposals fall short of conditioning the money on hitting the EU’s green goals, or explicitly excluding investments in fossil fuels.

What happens now?

Member state representatives in the Council have already begun poring over the Commission's Recovery Fund and MFF proposals. In parallel, the President of the European Council, Charles Michel, and his cabinet are consulting with the member states, who now hold the key to progress to the next stage. EU leaders meet next at the European Council summit on 19th June to thrash out an agreement. This will not be easy sailing and the storm is swiftly approaching. With the necessary unanimous agreement of the 27 member states, sign-off from the European Parliament, and the ratification process by national parliaments, all by 31st December 2020, there is not a moment to lose.

Last week’s proposals were a strong signal that the EU is serious about solidarity and fostering long-term growth and prosperity at home. While the Recovery Fund mainly serves to support internal cohesion, the von der Leyen Commission has demonstrated its commitment—at least rhetorically—to addressing global inequalities through the EU-led global pledging conference and the call for a global recovery initiative linking investment and debt relief to reach the Sustainable Development Goals. These are first steps towards a global leadership role for the EU. But, if it wants to have its voice heard in the world, there is no doubt that its strength has to start at home. The Recovery Fund and the MFF is the EU’s make or break moment both for its internal and external ambitions.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.