Earlier this week, the European Commission published its proposals on migration and border security for the next EU budget (2021–2027). Financial support for migration, asylum, and border management is to almost triple, from €13 billion to €34.9 billion. What might this mean for the EU and future migration flows?

Depending on the perspective, one could argue that the EU could not have picked a better or worse moment to publish its budgetary proposal for future migration management. This week, the EU states once again showed their inability to act in concert, with a humanitarian disaster unfolding on the Mediterranean as both Malta and Italy refused to accept a ship carrying 629 migrants. While Spain stepped in, offering safe harbour to the migrants on board the Aquarius, new Italian Interior Minister Matteo Salvini hailed the incident as a victory for his new government, sending a message to the rest of the EU that Italy is no longer prepared to be left dealing with migration flows in the Mediterranean. Since the EU-Turkey deal reduced the number of migrants arriving via the Balkan route, Italy has become the major destination for new arrivals at European shores.

More of the same or new priorities?

Is the new budget fit to deal with future migration challenges and how would it be allocated? Not surprisingly, and as a direct reflection of the huge influx of migrants in 2015 and 2016, the EU wants to strengthen its external border management with €21.3 billion, compared to €5.6 billion for the period 2014-2020. The Commission proposes the creation of a new Integrated Border Management Fund (IBMF) worth nearly €10 billion, with a good half of the funding allocated to member states’ long-term support for securing external land and sea borders and airports, as well as the common visa policy. In addition, more than 1 billion is reserved for “most cutting-edge customs equipment.” In short, the budget proposes a previously unseen amount of money to strengthen border control and enforcement.

Another €10.4 billion is allocated to the new Asylum and Migration Fund (AMF, currently AMIF), with the majority being long-term support for member states managing asylum, integration, and return. The remaining roughly 40 percent is assigned to a thematic facility, allowing for more flexible responses by the Commission in the years ahead. Besides increased support for resettlement and emergency assistance, funding is also allocated to support the “solidarity and responsibility efforts between the Member States,” addressing the lack of internal cohesion with regards to migration management.

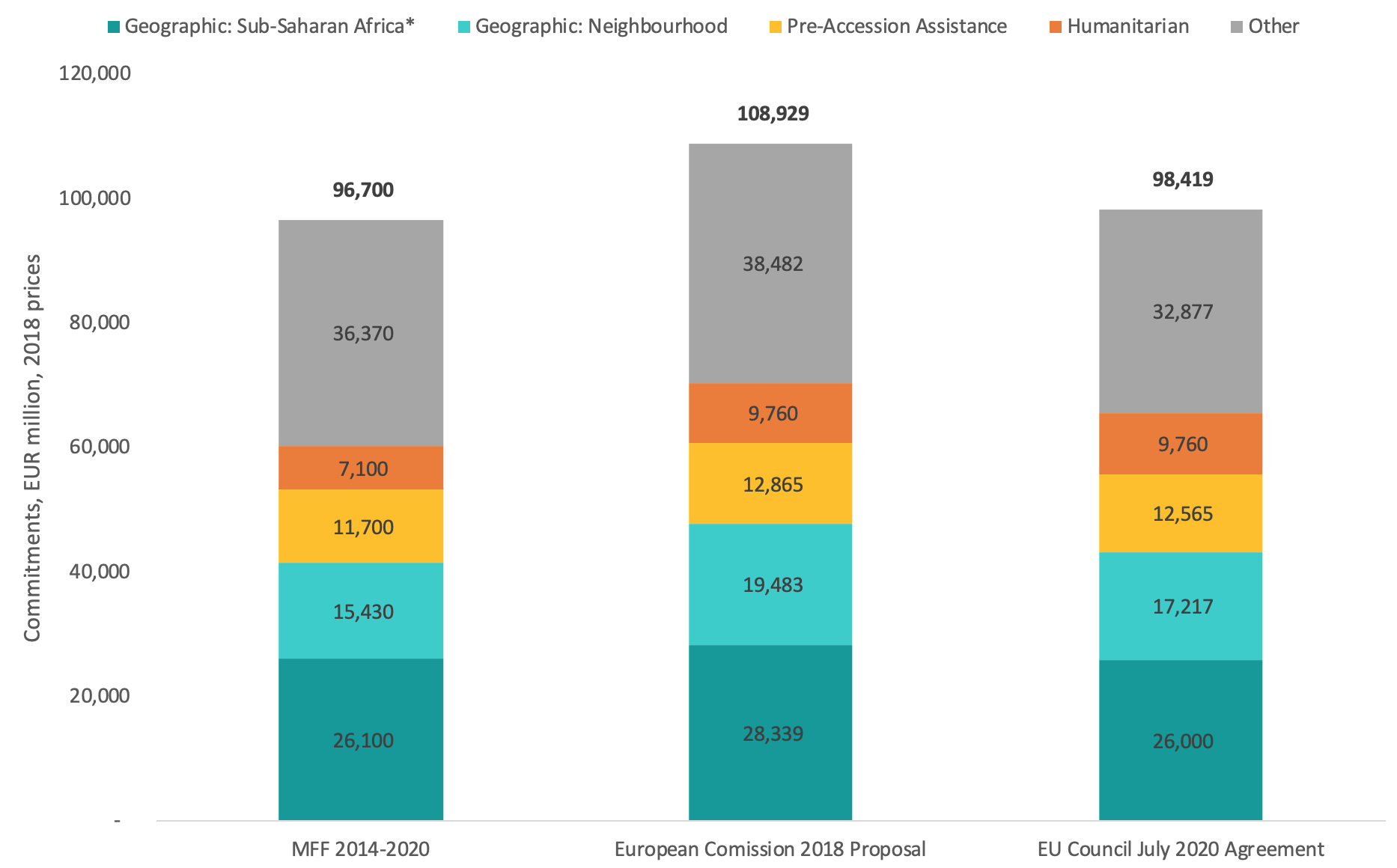

In the separately published funding proposals on the future of the EU’s international development budget, a spending target of 10 percent of the €28.9 billion Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument (NDICI) is dedicated to “tackle the root causes of irregular migration and forced displacement, in particular by promoting development and inclusive economic opportunities while creating conditions for legal migration and well-managed mobility,” without specifying how long-term legal migration and future mobility could be designed.

The proposals are clearly a response to the increased migration pressures on Europe in 2015 and 2016. The challenges posed by the large inflows of migrants could not be dealt with efficiently and effectively, in part because the EU’s funding instruments were not designed to support member states swiftly. Like the Commission’s proposal on European development cooperation, the new budget should allow for increased flexibility. Both the IBMF and the AMF, as well as the flexibility cushion in the new development cooperation instrument (NDICI), have a substantial amount of money reserved for emergency responses and flexible support for member states to address emergencies and emerging priorities.

However, learning from previous migration challenges seems mainly to have transformed into increased budgetary flexibility, not a more opportunity-based perception of migration. Rather, the Commission’s proposal seems to continue its reactive, limiting approach to migration. While the massive strengthening of external border controls—such as the introduction of a new standing corps of around 10,000 border guards and new equipment and better technology (i.e., EU-LISA), as well as better management of returns and readmission—might be justified to ensure EU member states deal with migration flows in a less tumultuous way, the budgetary proposals lack a vision for long-term, legal migration. Such a vision is necessary given the demographic challenges on both the European and African continents and is indispensable for one of the world’s development leaders.

More stability might lead to less migration—but economic development won’t

Especially at a time when the world faces one of the most substantial declines in global freedom in decades, the Commission’s commitment to the promotion of human rights and democracy in partner countries is significant. Europe remains one of the most important development actors, and its experience with democracy, the rule of law, and internal solidarity can and should be included in its work with partner countries, also by addressing the push factors of migration. Building resilient and supporting peaceful societies in partner countries is crucial, and evidence supports the underlying presumption that migration flows from Africa to Europe are partly driven by instability and conflict.

However, the approach of limiting migration by coupling external border management with promoting development and economic opportunities in partner countries will be only partly successful. The Commission claims that “increased coherence between migration and development cooperation policies is important to ensure that development assistance supports partner countries to manage migration more effectively.” In the absence of mechanisms for substantial legal migration to Europe, people seeking a better life will continue to be pushed into illegal migration. Evidence suggests that with growing economic opportunities, migration increases initially, until income levels reach a certain threshold. If the EU is successful in supporting economic development in its neighbourhood and the world, Europe’s political leaders should realise that this will raise future migration flows, especially from some African countries. So what should the EU do in order for its priorities in migration management to be successful?

Historical experiences suggest that the creation of legal pathways for migrants such as long-term labour market programs coupled with successful enforcement can work. While the creation and regulation of such programs remain mostly in the competence of the European national states, the EU misses an opportunity to acknowledge that there are currently hardly any legal pathways for third-state nationals to migrate to the European Union (students, highly-skilled individuals, and family reunion aside). The EU’s own Blue Card Directive, an instrument to attract more high-skilled workers, was not deemed efficient and the Commission’s action plan for an improved Blue Card directive has not gone very far in the current political environment. The new budgetary proposal’s failure to even refer to this program or to any other proposals for long-term labour market migration is astonishing given the demographic challenges ahead in both Europe and Africa.

The new budget on migration: More cohesion at best?

The Aquarius incident serves as a reminder of how much pressure the unresolved migration challenges put on the EU’s internal cohesion. There is major disagreement on the future of migration policy within Europe, with Southern European states disagreeing and a deep East-West divide, especially as Hungary, Poland, and the Czech Republic refuse to take part in resettlement efforts for a fairer European allocation of asylum seekers, leading to the Commission launching infringement procedures against these member states last year. The unprecedented increase in funding for border management in the MFF seems to reflect the “principle of hope” that more money will do the job in reducing internal tensions during the budgetary negotiations. However, in the long-term and given the absence of legal migration mechanism and the EU’s struggle to build a coherent asylum system by successfully revising the Dublin regulation, population growth, instability, and economic development in Africa could drive more people into risking the dangerous trip across the Mediterranean, irrespective of cutting-edge border management technologies.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Social media image by Ggia