The recent $5 billion overnight cut in UK foreign aid highlights the importance of understanding the politics of aid spending. For comparison, the 39 major private foundations who report their spending to the OECD spent a combined total of just over $7 billion in 2019. Should more private money go on advocating for higher government aid spending? This question is one being actively investigated by “Effective Altruist” groups, including Open Philanthropy and Giving What We Can.

One form of “advocacy” I’m particularly interested in is the role of international travel by rich country citizens to poorer countries in determining attitudes towards aid and development policy. Anecdotally, it might have been their first trip to Africa (for a Safari) that led to the foundation of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which now spends $3.5 billion a year. Systematic evidence is more mixed—my research finds that Mormons who are quasi-randomly assigned to poorer countries for 2-year missions aren’t necessarily more likely to be pro-aid than those assigned to go to Europe.

In 2007, the UK’s Conservative Party opposition development spokesperson Andrew Mitchell set up a “social action project” in Rwanda designed to build support for development in his party. In journalist Steve Bloomfield’s words, the project was:

“an annual two-week trip to Rwanda for Conservative Party MPs and activists ... As an aid project, Project Umubano is terrible. It’s gap-year-style volunteerism—building classrooms, teaching English, helping out in health clinics… But as a political project, it was genius. It attracted a stream of volunteers—ambitious would-be Tory MPs soon realised that a fortnight teaching English in a Rwandan village was a sure-fire way of getting yourself on the new A list for a safe seat. A decade on, the project’s alumni includes MPs, Lords and special advisers. Mitchell admits that helping Rwanda was only one aim of the project. ‘I introduced it, above all, to try to make sure that within the Conservative Party there is a core of people who are passionate about development.’”

Last month, Andrew Mitchell led a rebellion in the House of Commons against his own party in the vote on the cuts, which ultimately gained only 25 Conservative Party supporters, 18 short of the 43 needed to stop the cuts. Clearly “a core of people who are passionate about development” isn’t enough to stop a new party leader who just isn’t interested.

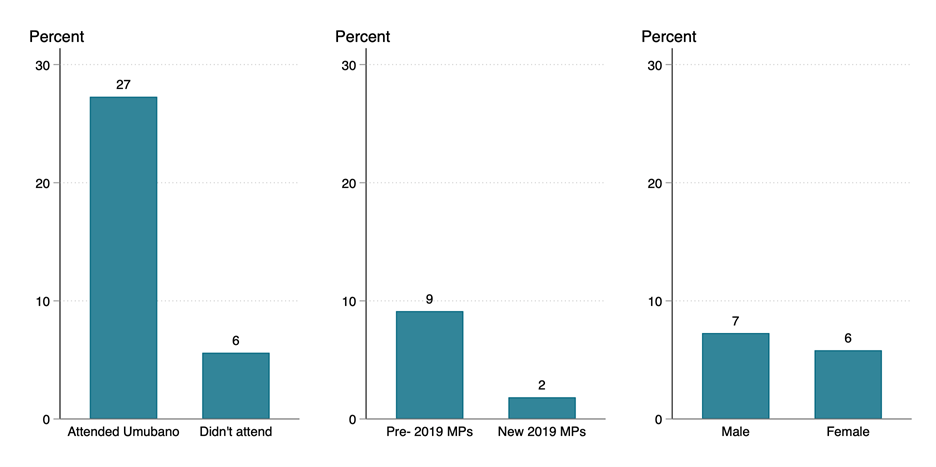

According to my count, 22 current MPs had attended Project Umubano. Of these, six voted against the cuts and 16 voted for them. Attending the project clearly didn’t sway every vote. Stiil, those who attended Umubano were much more likely to vote against the cuts (27 percent of them) than those who hadn’t (only 6 percent of them). This correlation is also not entirely causal; those more interested in development to begin with will have been more likely to volunteer for a trip in the first place. Hence, we can perhaps consider this to be an upper bound—a 22 percent increase in the probability of a Conservative MP voting against aid cuts, or a gain of five votes. The rebels are also much more likely to have been existing MPs prior to the first election under Boris Johnson in 2019. Those newly elected are less likely to vote against the government under any circumstances, as they don’t want to ruin their chances of getting a Cabinet job (and only 1 of the new cohort of over 100 had attended Project Umubano). Nine percent of pre-2019 MPs voted against the cuts, compared to just two percent of new 2019 MPs.

Figure. Percent of Conservative MPs who voted against aid cuts

Whilst public opinion no doubt plays some role in constraining decisions, this one was entirely political, and ultimately depended on the views of the Prime Minister and his Chancellor. But who becomes the next Prime Minister is always uncertain, and there’s a small chance it could have been one of those five MPs converted to a pro-aid position by their trip to Rwanda or Sierra Leone (five that is, if we make the heroic assumption that the correlation between attendance and voting patterns is causal). Perhaps, then, we shouldn't judge a project by its unsuccessful ex-post outcome, but by its ex-ante expected value. Those five MPs are 1.3 percent of all Conservative Party MPs. If there is a one percent chance of one of them becoming Prime Minister, a one percent reduction in the risk of a $5 billion annual cut is worth $50 million per year in expected value. I don’t know what Project Umubano cost, but I’d presume a lot less than that.

Is it worth investing in advocating with MPs for more aid? On this evidence, the jury is still out on the value of volunteer trips. But the potential payoff is so big it would seem foolish not to try something.

The data on which way each MP voted, and who participated in Project Umubano, is available here.

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise.

CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.