Recommended

In 2018, the Trump administration and lawmakers from both sides of the aisle found common cause: a desire to strengthen US development finance tools led to passage of the BUILD Act, which established the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC). The varied interests that fueled DFC’s bipartisan creation story have raised the agency’s profile compared to its predecessor, the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC).

As a result, DFC has been the subject of a growing list of proposals from lawmakers that envision the agency tackling a wider range of challenges than initially envisioned. The agency may find ways to leverage this heightened interest. However, delivering on the bipartisan, foundational vision for DFC amid evolving US foreign policy priorities will require a laser focus on impact and fidelity to DFC’s core development mission. To complement the agency’s affirmative agenda, DFC leadership should consider developing clear guidelines to guard against mission creep, maximize mobilization of private sector financing, and avoid crowding out private finance. Moreover, setting up DFC for success entails resourcing the agency appropriately and recognizing that other arms of the US government (for instance, the Export-Import Bank) and key multilateral organizations may be better equipped to tackle certain policy objectives.

DFC’s mandated focus on lower-income countries and early track record

The BUILD Act mandates DFC to focus its operations in low- and lower-middle-income countries (LICs and LMICs), where its support is likely to have the greatest development impact. The statute enables DFC to operate in upper-middle-income countries but specifies that projects in these settings must meet qualifications related to furthering both US foreign policy interests and development. The act itself is silent on the question of whether financing can be directed to high-income countries. However, an omnibus spending bill passed by Congress in December 2019 included the text of the European Energy Security and Diversification Act, which provides explicit authorization for DFC to pursue energy security projects in high-income countries in Europe, as well as in upper-middle-income countries without the development justification typically required. More recent legislative proposals have likewise sought to broaden DFC’s remit—enabling or directing the agency to invest in higher-income economies without a clear development rationale.

This has raised concerns among members of the development community, especially stakeholders who recall the criticisms leveled at the once-embattled OPIC that helped inform the BUILD Act’s insistence that DFC prioritize development impact. Diverting DFC’s attention and investments to richer countries isn’t strategic, given that high-income countries (HICs) can largely mobilize private sector financing for viable projects without outside help. Moreover, the marginal dollar DFC can provide in these countries will be insufficient to subsidize a project’s bankability. In contrast, in LICs or LMICs, where capital markets aren’t well established and access to finance is a binding constraint, DFC’s marginal dollar can have an outsized impact. That dollar also represents a far greater proportion of the country’s economy. In addition, standard DFC projects are expected to have a strong development rationale and drive some measure of social or political change. In HICs, the prime rationale is likely to be driven by national security priorities with only a secondary development mission, if present at all.

It’s important to interrogate how DFC support will provide added value HICs—beyond the symbolic—and to what extent investments in higher-incomes contexts will divert attention from LIC and LMIC economies where development finance is needed most.

Charting a course for DFC

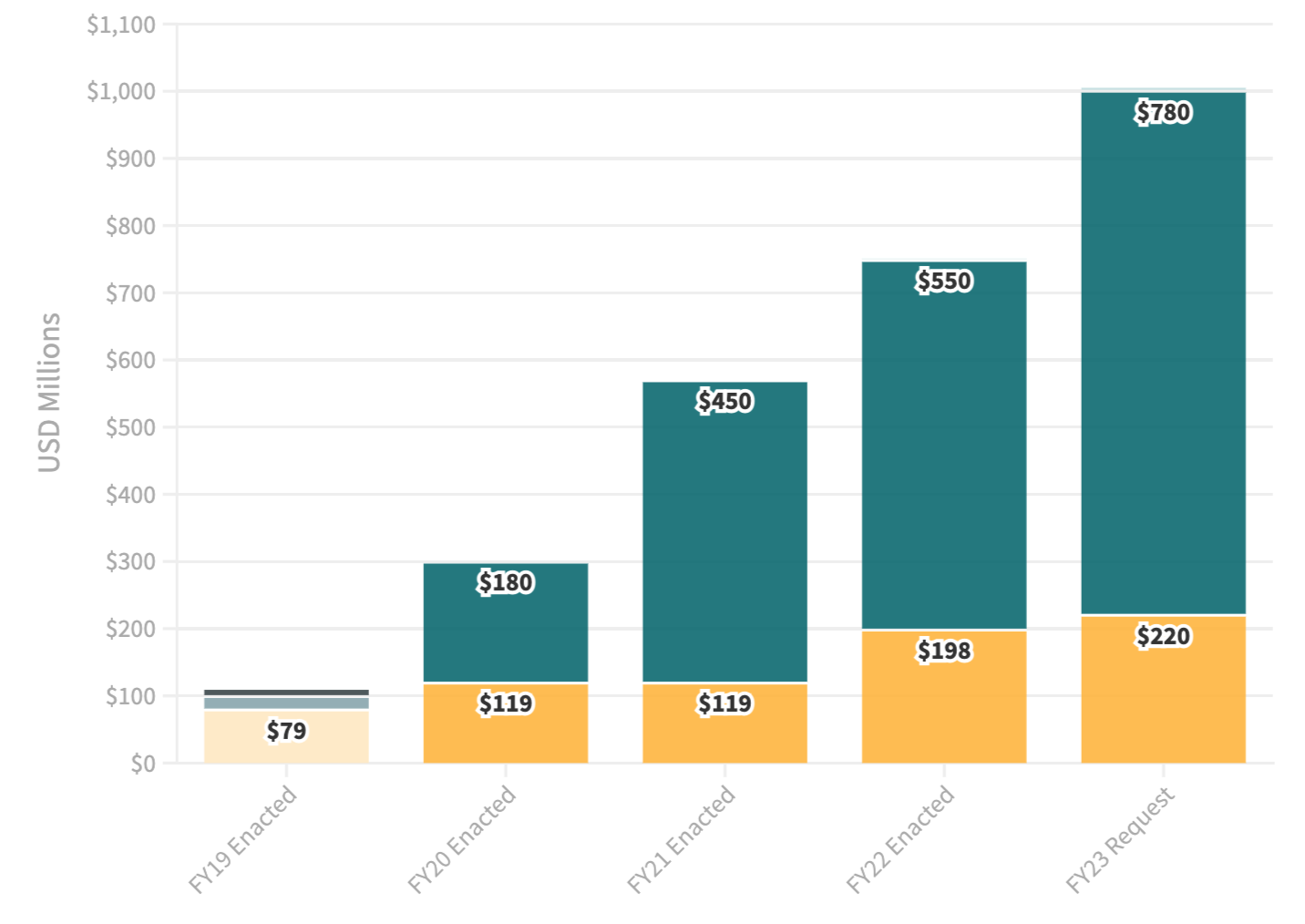

Since opening its doors, DFC has sought to both grow and rebalance the portfolio it inherited from OPIC. In 2021, DFC’s commitments have totaled $6.7 billion, a near doubling of OPIC’s annual lending and investments. This includes significant growth in the value of projects in lower-income countries, but upper-middle-income investments remain a substantial share of the agency’s annual commitments.

Figure 1. DFC’s annual commitments far outpace OPIC’s

Source: DFC Transaction Data

The task for DFC’s leadership is to establish clear guidance and guardrails that can help ensure the agency retains a strong development focus and maximizes impact. While the agency has outlined a vision for an affirmative development-oriented agenda, DFC leadership should also set a high bar for projects that are not directly within its core mandate, helping to ensure that projects favored on the grounds of national security symbolism rather than development impact don’t derail DFC’s progress. To do this, the agency’s leadership could set limits and expectations to guide any investments in higher-income countries. Adopting a transparent and impact-driven approach to emerging priorities would strengthen the DFC’s reputation for development rigor and could ameliorate concerns raised by some of the agency’s chief supporters. What follows is a non-exhaustive list of factors the agency could consider.

Limits on share of portfolio or commitments

DFC could consider limits on the share of its portfolio or share of annual commitments in high- and even upper-middle-income countries. For added flexibility, the agency could consider using a multiyear rolling average. For instance, setting out to ensure the HIC/UMIC portfolio does not exceed 30 percent of DFC aggregate exposure over a five-year period.

In addition, and taking inspiration from the Impact Quotient, DFC could outline specific criteria it would look for among projects in higher-income countries, which would focus on spillover development benefits and global public goods. These might include:

- Innovations in business models and technologies that will promote inclusive and sustainable growth with plans to facilitate their transfer to LICs and LMICs. (e.g., drone service delivery, use of GPS data for commercial purposes, more efficient batteries.)

- Investments that strengthen regional integration in ways that demonstrably benefit poorer countries in the region.

- Financing that will facilitate standard-setting, in areas such as data privacy, with a deliberate strategy for improving policy and practice beyond the country where the investment is made.

- Investments that build resilient supply chains for certain essential goods and services (e.g., for vaccines, therapeutics) that benefit LICs and MICs as well as HIC recipient countries.

Mobilization requirements

DFC could set a cap on its share of investment relative to total financing mobilized, for instance setting a significantly higher bar for mobilization of private finance in HIC projects than for LIC or MIC projects. This would require DFC to be more catalytic in HICs where capital markets are deeper and private financing more abundant than in less established markets.

More equity/guarantees

DFC could limit direct loans in high-income countries, instead prioritizing equity investments and guarantees, which are more likely to be catalytic. Equity would mobilize more private finance per dollar of taxpayer resources (as would guarantees) and should provide a higher return on investment. (Realizing much of this leverage potential hinges on adjusting the current budget treatment of direct equity investments as noted below.) The case for loans in HICs—where financial intermediation is strong and governments have their own available resources—is not evident.

Time limits on investment positions

DFC could set defined exit targets for investment positions in higher-income settings and set a maximum loan and guaranty tenor. This would ensure that DFC’s capital does not remain tied up for long periods in HICs and that the agency has a plan to exit these markets.

Take on more risk

DFC could invest in earlier-stage, first-mover projects in HICs with strong potential positive spillovers, while capturing associated higher returns.

By establishing clear guidance while retaining sufficient flexibility to account for shifting demands, DFC leadership can provide a critical steer to help ensure the agency delivers impact by crowding in private finance where it’s needed most. In communicating these (or other) guiding investment standards to lawmakers, leadership should emphasize the need to deliver results, not talking points, amid potentially competing priorities. DFC also will need to manage expectations to avoid facing the criticisms leveled at its predecessor, OPIC.

Expanding DFC’s capacity requires resources

As DFC works to expand its portfolio and deliver on a growing list of policy demands, it will be important that Congress provides the agency with the resources it needs to staff up and support greater deal flow. In addition to appropriating funding, Congress can enable DFC to better leverage its program account by directing a fix to the illogical budget treatment of direct equity. The current arrangement, which treats the use of equity like a grant, fails to appreciate the nature of equity investments and recognize OPIC’s long track record of making similar investments without an equity stake. This approach makes little sense and puts unneeded pressure on the international affairs budget. Lawmakers have also entertained the possibility of increasing DFC’s portfolio cap from $60 to $100 billion—signaling even greater ambition for the agency.

Alternatives to DFC financing

At its core, DFC is a development agency focused on private sector engagement. But DFC’s unique set of tools—with its promise of offsetting collections—continues to attract interest from lawmakers and administration officials looking to pursue a range of policy objectives. That fact raises important questions about the adequacy of the broader US foreign policy toolkit. Congress and the administration should explore alternative means of tackling various international policy goals, considering opportunities for increased leadership, renewed commitments, and reform.

Multilateral development banks

The United States is a top shareholder in several key multilateral development banks. The MDBs have the benefit of strong country partnerships and financial leverage that can unlock tremendous lending capacity. The US could look to exercise greater leadership in its contributions to—and in shaping the ambitions and policies of—these institutions to respond to the investment needs of UMICs that the DFC is ill-placed to prioritize.

Sovereign loan guarantees

An existing US sovereign loan guarantee program dates back to the early 1990s but remains an underutilized instrument. As an approach, sovereign loan guarantees offer great leverage potential—allowing for scale—and can be deployed quickly and efficiently relative to more traditional aid. Congress and the administration could revive and inject new purpose into the sovereign loan guarantee program—grounding its revitalization in tackling critical development issues, such as advancing food security, promoting clean energy transitions, and supporting economic recovery, while providing an alternative to Chinese overseas financing.

Export-Import Bank

Ex-Im is the United States' official export credit agency. While not a development agency, and at times maligned, Ex-Im boasts financing tools and insurance products and may be better positioned to pursue certain policy objectives overseas, again especially in UMICs and HICs. Congress could work with the administration to ensure that Ex-Im has the authority, resources, and flexibility to serve US interests overseas and provide competitive financing to support national security goals.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.