Recommended

Blog Post

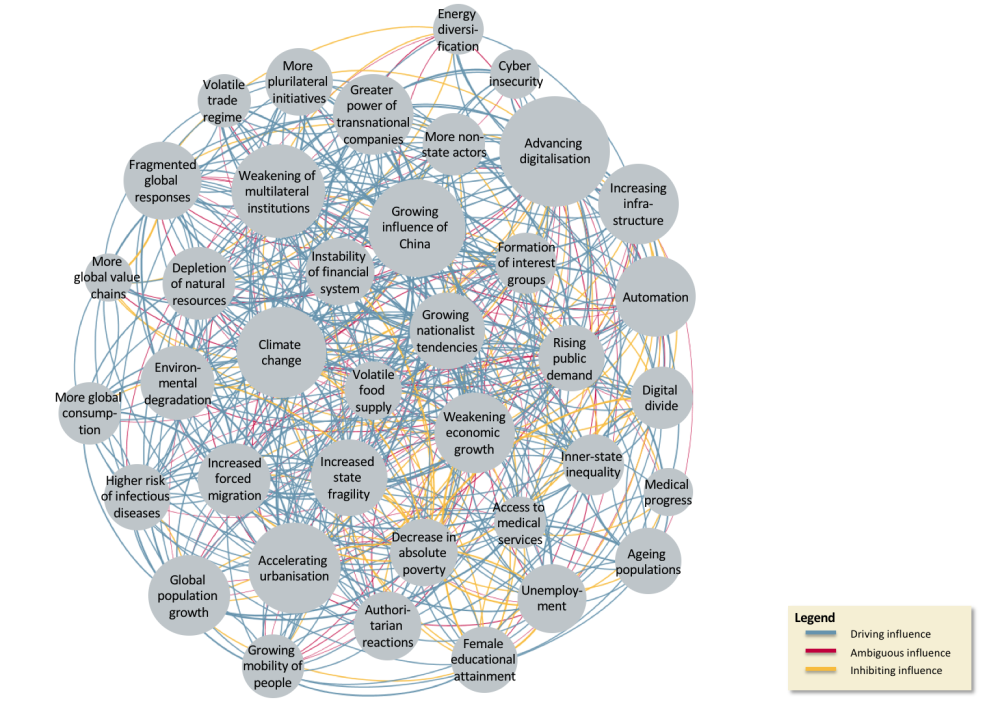

Official bilateral and multilateral development agencies are under strain from opposing forces: on the one hand, they are confronted with a world in which the development challenges are interconnected and daunting, and the risks are systemic and increasing; on the other, they are grappling with a world in which ardent nationalism, protectionism, and populism are rising, and rules-based multilateralism is declining.

The Web of Global Interconnections

Source: German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development, presentation at CGD Development Leaders Conference, 6-7 November 2018

This was the backdrop to a gathering of development agency leaders hosted by CGD in London last week. The sense of urgency was unmistakable—if the development community proves unable to respond rapidly, effectively, and collectively, the progressive gains made over the last decades are likely to unravel.

Rethinking strategy and approach

In the face of this complexity and uncertainty, development agencies are grappling with their responses. They are trying to focus on what they are good at—rooting their strategies in their own values and experiences as nations—but realising that today’s increasingly complex, multifaceted and interconnected challenges and needs require different models and mindsets, different partnerships with the public and private sectors, different skills and capacities, and stronger leadership across government. Nevertheless, it continues to be the case that national political will, rather than global need, shapes their investment.

Organising to deliver effective assistance

Development agencies are reorganising themselves to reflect strategic orientation and policy priorities, with refutable evidence on the optimal structure for managing development. The institutional architecture for managing development cooperation varies across countries and changes over time. There are, essentially, four types of organisational models in existence across the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC) donor countries:

-

a fully integrated model whereby the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is responsible for development policy and implementation, e.g. Denmark

-

a semi-integrated model whereby a Development Directorate within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is responsible for policy and implementation

-

a hybrid model whereby the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has overall responsibility for policy and a separate executing agency is responsible for implementation; and

-

an autonomous model whereby a Development Ministry is responsible for both policy and implementation.

Although most agencies are now integrated into the Ministry of Foreign Affairs with development directorates responsible for policy and implementation, there is no evidence to suggest that one specific institutional model is better than any other in the delivery of more effective development assistance, nor that any one model is more conducive to integrating development across other areas of government.

Avoiding a race to the bottom

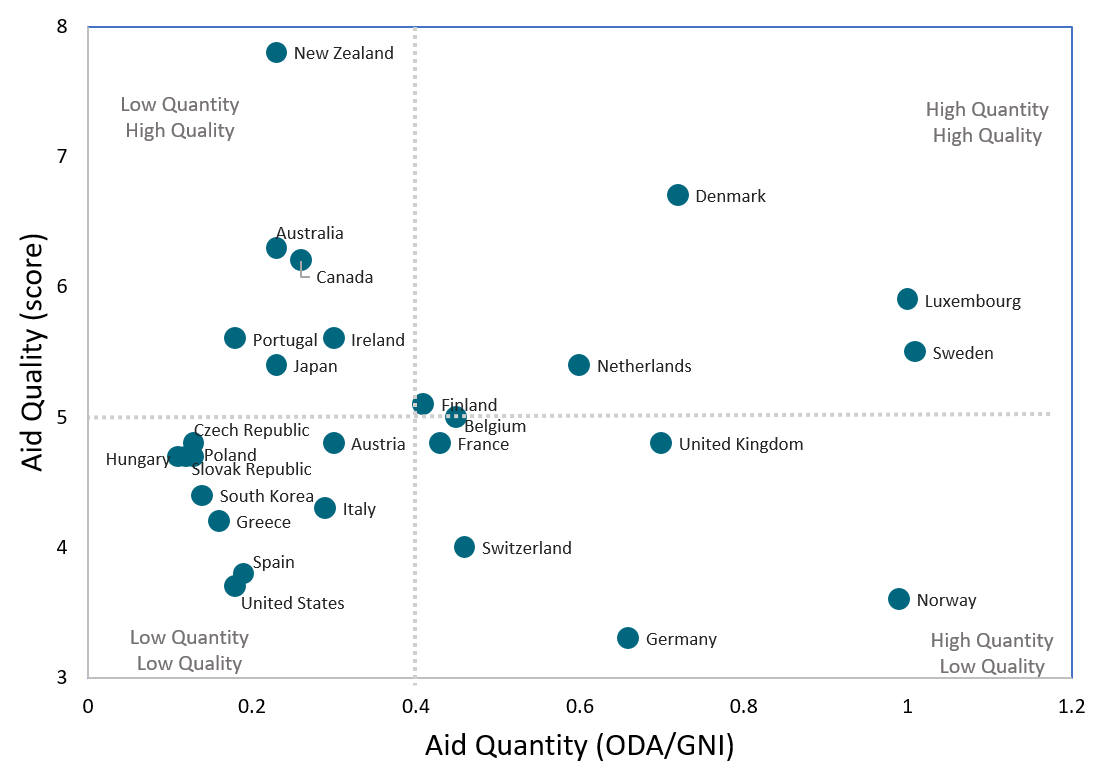

Development leaders are consistently talking about innovation, but they are finding it increasingly difficult to be innovative with taxpayers’ money. They beat the drum for flexibility, but they continue to earmark. Achieving results at scale is a huge challenge. They are trying to come to terms with the rise of newer and emerging actors on the scene with their different approaches and models of cooperation, operating outside of the normative framework for what constitutes effective development. And even amongst members of the DAC that have been aligned on how to measure development effectiveness since the Paris Declaration in 2005, in practice, there is huge variation in quality.

Alignment and ownership principles are not taken seriously. Some DAC members are reluctant to use country systems and have abandoned modalities such as budget support. Aid continues to be tied, because tying is a good recipe to generate more aid and because its use compels others to tie aid. Even countries that claim to have 100% untied still de facto tie based on the proportion of contracts that are awarded to companies from the donor country. Development agencies have struggled to convert principles into action and the threat of “a race to the bottom” looms large. The message was clear: having a set of principles we’re not sticking to is a bad state of affairs. The reality is that the development landscape has changed drastically since the turn of the century and with it, the consensus on development effectiveness. It is time to adapt the norms and standards to fit the time we’re in, and to halt the race to the bottom.

Dealing with the pressure of nationalist forces

As development agencies struggle with these challenges, across the developed world, popular trust in bureaucratic institutions is declining and populist nationalism continues to grow in strength and influence. Development agencies are looking to draw “win-wins” where the domestic and international objectives align across all interventions. It is, however, unclear as to whether this actually entails a redirection of investment and assistance or merely a reframing of intention to garner public support.

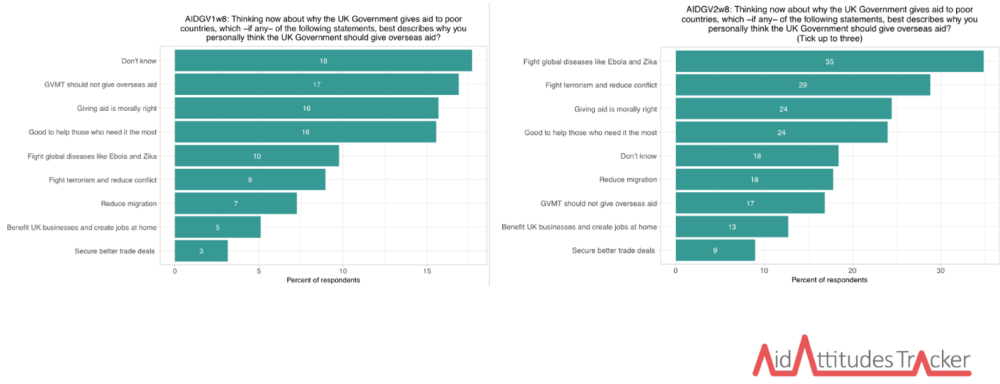

But what does the public really think and what resonates? The latest poll from the Aid Attitudes Tracker shows that support for aid is still strong in Germany and France, mixed in the US, and low in the UK. Close to half of British respondents said that the aid budget should be reduced. Interestingly, it also shows that political affiliations don’t matter as much as values in terms of support for aid. In the UK one in three people support the objective of helping people in poor countries for moral reasons over that of giving aid in the national interest. However, when breaking down the concept of the national interest into fighting global diseases, fighting terrorism and reducing conflict, reducing migration, benefitting UK business and creating jobs at home, and securing better trade deals, disease and terrorism trumps the moral imperative. The bottom line, however, is that aid is not a burning issue: it is not something the public generally thinks about. But when people do think about it, they do so in a way which rests on their own values and world orientation.

Source: Aid Attitudes Tracker, presentation given by David Hudson, Professorial Research Fellow in Politics and Development, University of Birmingham, at the CGD Development Leaders Conference, 6-7 November 2018.

Given these results, how should development agencies communicate with the public to bring it along with them? The message from the polling is clear: we need to fundamentally tell better stories and make them tangible to people, showing specifically how an intervention makes a difference. But giving people numbers, like “six million girls now in school,” will not resonate. And it’s important to get the “fairness” message right about why poverty elsewhere is important compared to poverty at home.

Continuing the conversation

The big takeaway from this year’s Development Leaders conference was that all agencies, new and old, face similar challenges—of relevance, responsiveness, communication, capability, and resilience—and there is much to learn from sharing experiences, especially at this time of profound change in the world of international development. But we should also not lose sight of our past successes and of the fact that the development agency of the future has a critical role to play in addressing the world’s challenges.

It was Max Roser who said “Our perception of how the world is changing matters for what we believe is possible in the future. Those who don’t expect that things get better in the first place will be less likely to demand actions that can bring positive developments about. The optimists on the other hand will want to see the necessary changes for the improvements they are expecting.”

The task for the future development agency is to identify the weak spots of the existing order and forge coalitions of the willing to address them.

To receive updates about next year’s conference planned for Beijing sign up here and make sure to put a check mark next to Sustainable Development Finance.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.