I recently delivered a presentation (PowerPoint download) to students in the Master of Public Administration in International Development program at Harvard’s Kennedy School. The purpose of my presentation was to use two cases of IMF-supported program conditionality to animate a discussion of the bridge between first-best policy advice and on-the-ground development policy in country-specific political economy contexts. Having been involved as Minister of Finance in the Liberia case, and as Director of the Fund’s African Department in the Mozambique case, I was able to approach the issue from both an outside- and an inside-the-IMF perspective. Below are the three main conclusions of my presentation.

Country Specifics Matter

The Fund understandably seeks to help achieve first-bests in its member countries through surveillance and policy advice, as well as conditionality agreed with them. And much of this is based on the Fund’s deep expertise on what works and what doesn’t, obtained through its vast cross-country experience. But it is ultimately country-specific circumstances that determine how and when that advice gets played out, or whether it is circumvented.

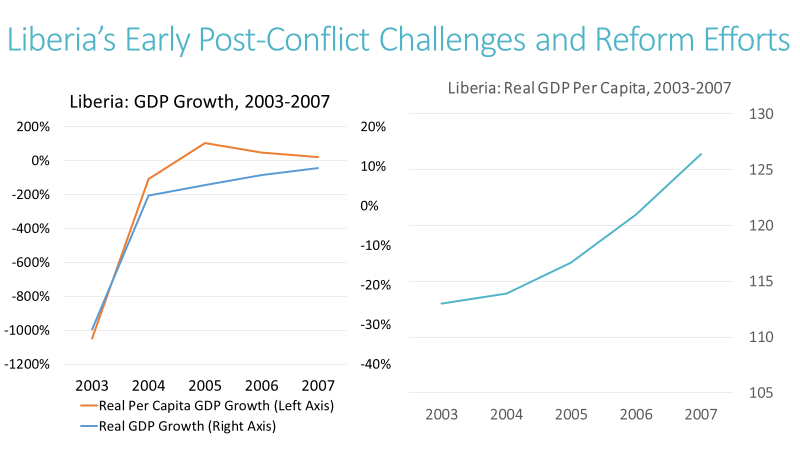

In Liberia, merging the then-autonomous Bureau of the Budget (BoB) with the Ministry of Finance was drawn out with difficult politics and conditionality for more than two years. The Fund didn’t hesitate to step in as the “heavy weight” in the domestic bargaining around the merger and made the tricky choice of betting on it. The integration was ultimately made possible not simply by virtue of its merits, but also by the confluence of self-interested parties and the overriding search for debt relief. While President Sirleaf undoubtedly had other good reasons for selecting the BoB Director-General as Minister of Finance, it was clearly not simply a matter of coincidence that this decision eased resistance to the merger.

But So Does Transparency

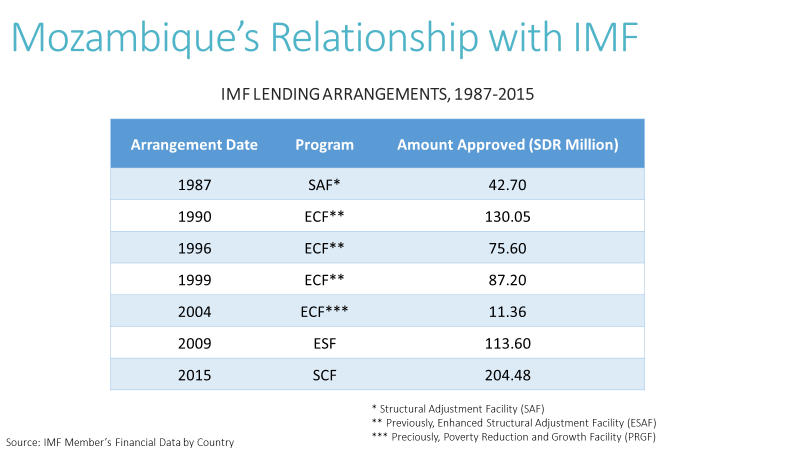

With its undisclosed borrowing, Mozambique deceived its people, its parliament, and the Fund. It blew up the “Mozambique Rising” story and the notion that the country was an example for others. By concealing a large volume of nonconcessional debt, Mozambique circumvented continuous Policy Support Instrument (PSI) conditionality to not exceed the ceiling for contraction of such debt and its Article VIII obligations. In doing so, the authorities rendered the vested interests of defense, security, and state-owned enterprises paramount. Fully owned transparency is clearly a sine qua non for trust and true partnership, which were damaged in their absence.

There has, I’m sure, been more soul-searching in the Fund about the Mozambique case since my departure. An important takeaway from the Mozambique case is that while deeper understanding of vested interests and the political economy context can undoubtedly enhance the Fund’s effectiveness, if countries are deliberately deceptive, the Fund—or any other institution for that matter—can still be blindsided, even after 30 years of deep surveillance, tracked conditionality, multifaceted technical assistance, and on-the-ground presence.

Conditionality and Country Interests Must Align

But the most important takeaway I see from these two episodes is that conditionality is most powerful and effective when aligned with what country authorities most cherish at a particular point in time. Liberia was focused on debt relief and was willing to turn over rocks to achieve it. Convinced that it was “rising,” Mozambique was, for its part, willing to risk deceiving the Fund to satisfy vested interests and address perceived defense/security needs.

*I am grateful to Kelsey Ross for research assistance.

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise.

CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.