The IMF established the Resilience and Sustainability Facility (RSF) in 2022 with the objective of extending financial support to countries tackling climate change and preparing for pandemics. Since then, five RSF programs have been approved by the IMF board: Bangladesh, Barbados, Costa Rica, Jamaica, and Rwanda. More countries are reportedly negotiating with the IMF to gain support from RSF.

To tap RSF support, countries are required to have high-quality policy measures in climate transition and pandemic preparedness, as well as a parallel IMF-supported program (with or without financing) with “upper credit tranche” (UCT) quality policies. The UCT policies are meant to help countries resolve their balance of payments problems and achieve external viability in the medium term. In addition, these policies should ensure that the country can repay the IMF.

We argued in a recent paper that the bulk of measures included in the first five RSF programs are low depth, meaning that they may not bring about durable institutional and policy changes to mitigate and adapt to climate change. (None of these programs focused on pandemic preparedness.) During the Spring Meetings, the IMF managing director announced that an additional 44 countries have expressed interest in borrowing from the RSF, and called for more resources for the resilience facility.

It will be challenging to increase RSF recipient countries by another 44 in the near term for two reasons. First, countries with IMF programs since 2000 have averaged 44 and it would be unrealistic to expect all program countries each year to seek assistance under the RSF. Second, expanding countries with IMF programs without financing is improbable as it would imply a major change in how countries perceive the stigma ascribed to an IMF program.

Countries with IMF lending

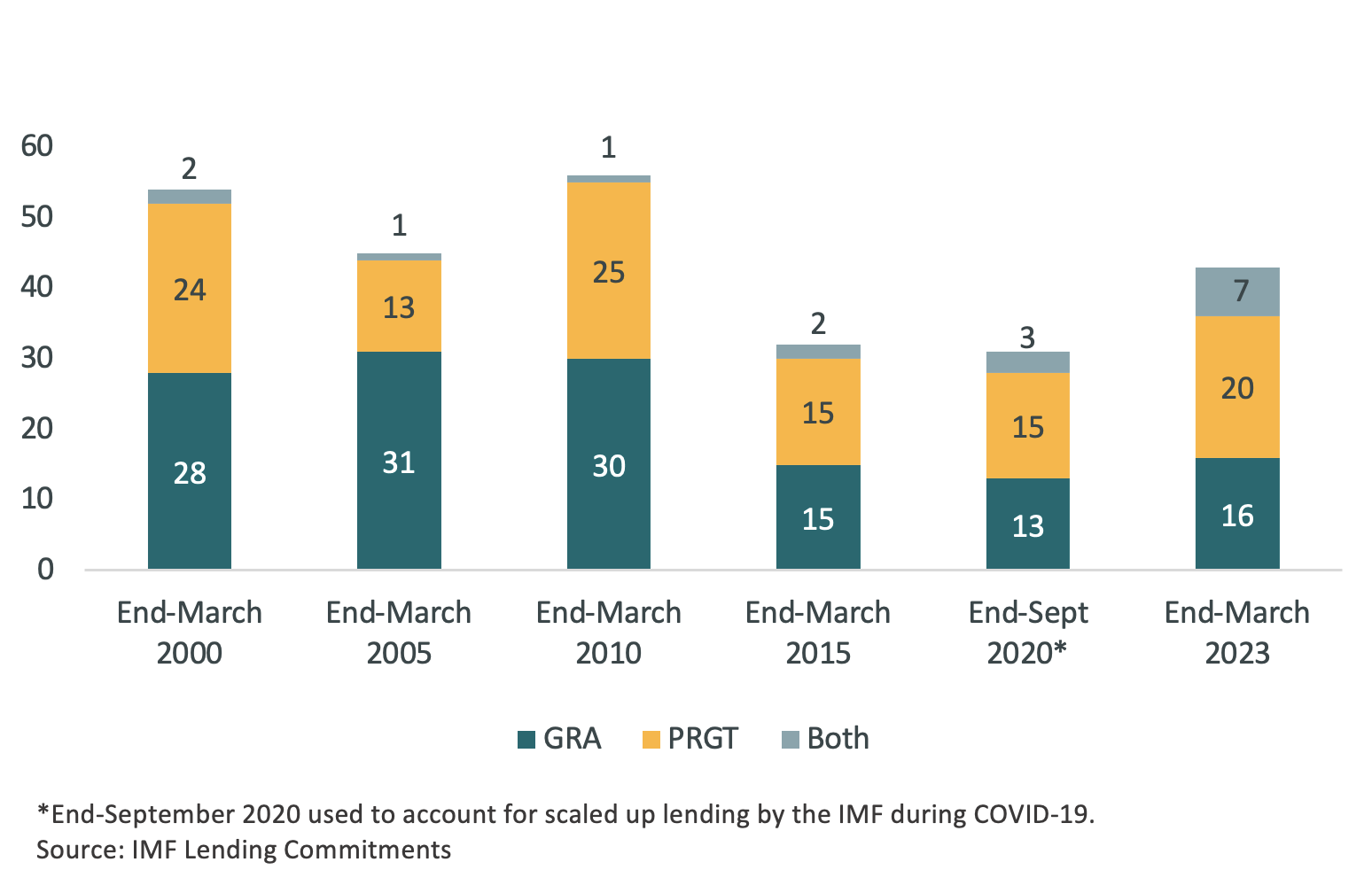

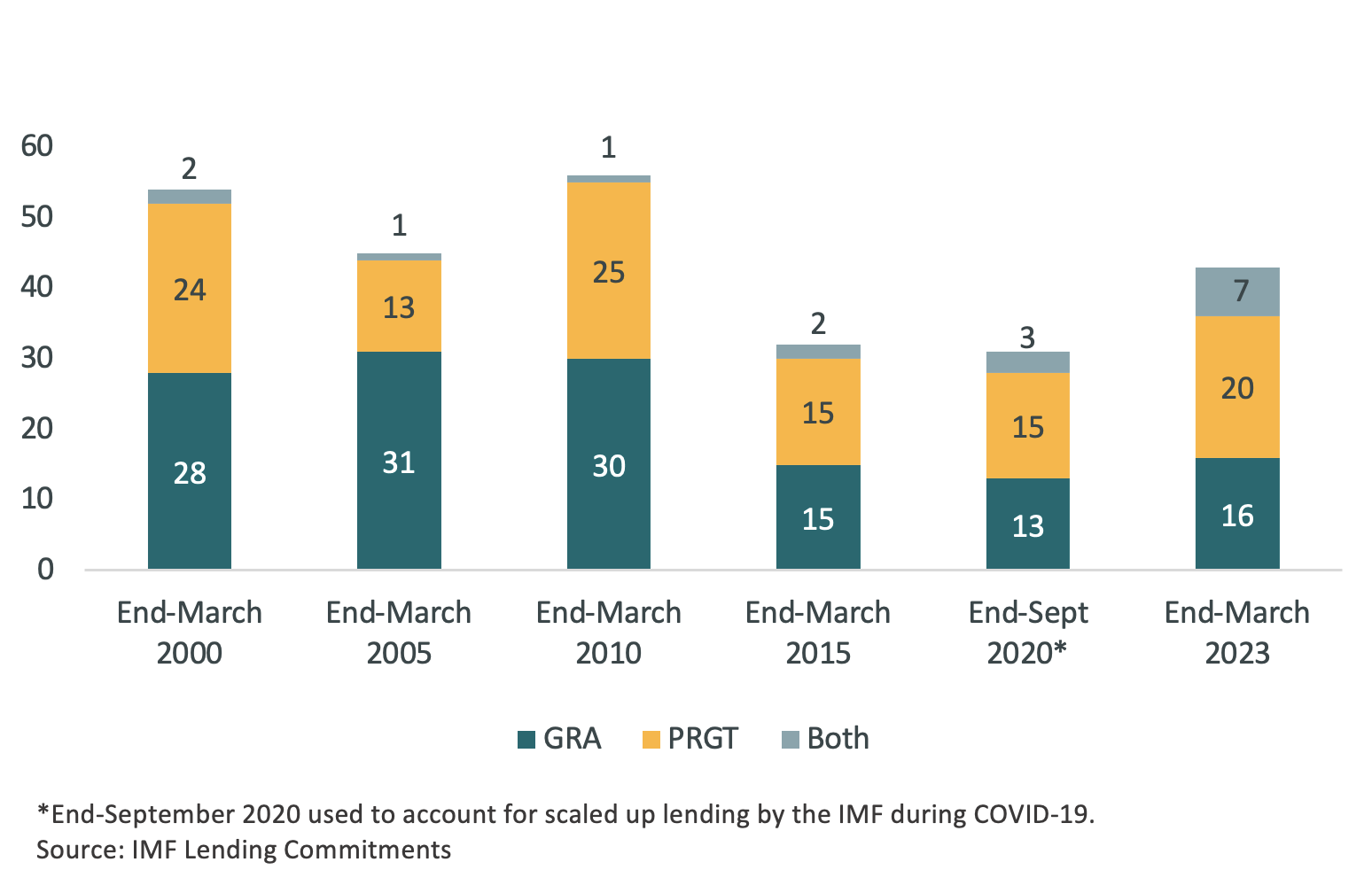

During 2000-2023, countries that obtained financial assistance from the IMF varied between 31 in 2020 to 56 in 2000 at the peak of the financial crisis (Figure 1). At the end of March 2023, the IMF had financial arrangements with 43 countries. Programs have been split equally between the two financing sources, the General Resources Account (GRA) and the Poverty and Growth Reduction Trust (PRGT), except in 2005, when GRA programs were more than double that of PRGT. Among already-agreed RSF programs, almost all are funded by GRA. A country could also enter a program with the IMF with no financing to secure endorsement of its policies.

The five RSF programs have been accompanied by Extended Fund Facility (EFF) (Barbados and Costa Rica) funded by GRA; Extended Credit Facility as well as an EFF (Bangladesh) with support from both GRA and PRGT; Policy Coordination Instrument (Rwanda) which is a non-financing instrument; and Precautionary Liquidity Line (Jamaica) funded by GRA.

Countries with active IMF lending commitments

Potential RSF programs

Of the 43 countries with IMF programs at the end of March 2023, four already have RSF programs. One RSF country has a board-endorsed program without financing. This leaves 39 countries with existing programs that could potentially draw on RSF financing.

However, several program countries are unlikely to request RSF support (e.g., Chile and Mexico) because they prefer precautionary arrangements and do not immediately need balance of payments financing. There are other countries that are deeply embroiled in stabilizing their economies (e.g., Sri Lanka) and are unlikely to have sufficient policy coherence on issues related to climate change and pandemics to put forward an RST. Fragile states (e.g., Somalia) are in a similar boat.

It is implausible that countries will request an IMF program with financing, just to get financing under the RSF. So, a large expansion in RSF programs is only likely if many more countries request IMF programs, including those without financing to meet the requirement of “upper credit tranche” conditionality. But this would represent a sea change in how countries perceive IMF programs. It would be a major achievement of the RSF if countries would no longer attach stigma to an IMF endorsement of their economic policies

Other concerns with a rapid scaling up of RSF remain. The quality of measures included in the initial RSF programs has not been as deep as other IMF programs supported by GRA and PRGT financing. In part this is attributable to a lack of sufficient diagnostics on needed reforms on climate change mitigation and adaptation. Accelerating the number of programs in the short term would leave insufficient time to conduct appropriate diagnostics by countries, the IMF, the World Bank, and other partners.

Bottom line

The IMF should be applauded for implementing a new facility at highly concessional terms to support the long-term challenges of climate change and preparing for pandemics. That said, it is highly improbable that extending RSF financing to an additional 44 countries will be feasible in the next one or two years as it would require a major change in the mindset of borrowing countries about using IMF facilities and a huge effort by already-overstretched IMF staff.

We wish to thank Benedict Clements and Mark Plant for helpful suggestions.

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise.

CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.