After weeks of speculation, the European Commission has published the details of its proposed radical reconfiguration of EU external actions instruments for the 2021-2027 Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF). On the face of it, it’s ambitious in numerical terms, global in geographical reach, sweeping in thematic focus, and daring in flexibility. There’s something for everyone in this budget. Digging into the details, however, while value-add is the mantra, what’s missing is a distinctive EU development offer. And while flexibility is key in an increasingly turbulent and uncertain world, it needs to be deployed using clear guidelines and balanced by accountability.

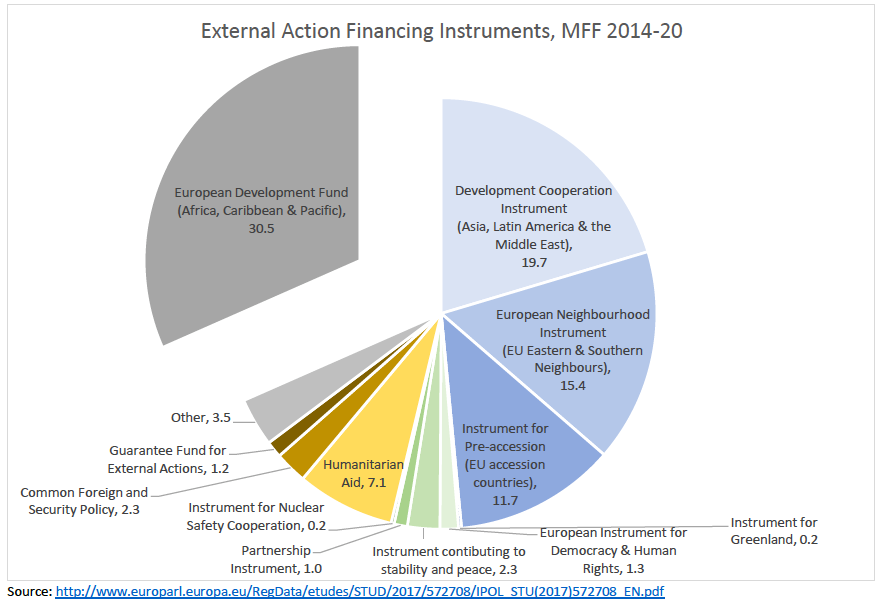

In brief, the restructure entails halving the number of EU external financial instruments from 12 to 6 and integrating most of the current instruments into a souped-up single Neighbourhood, Development, and International Cooperation Instrument of almost €90 billion. The rationale: simplification, flexibility, and coherence—and according to the Commission, “a budget fit for the future.”

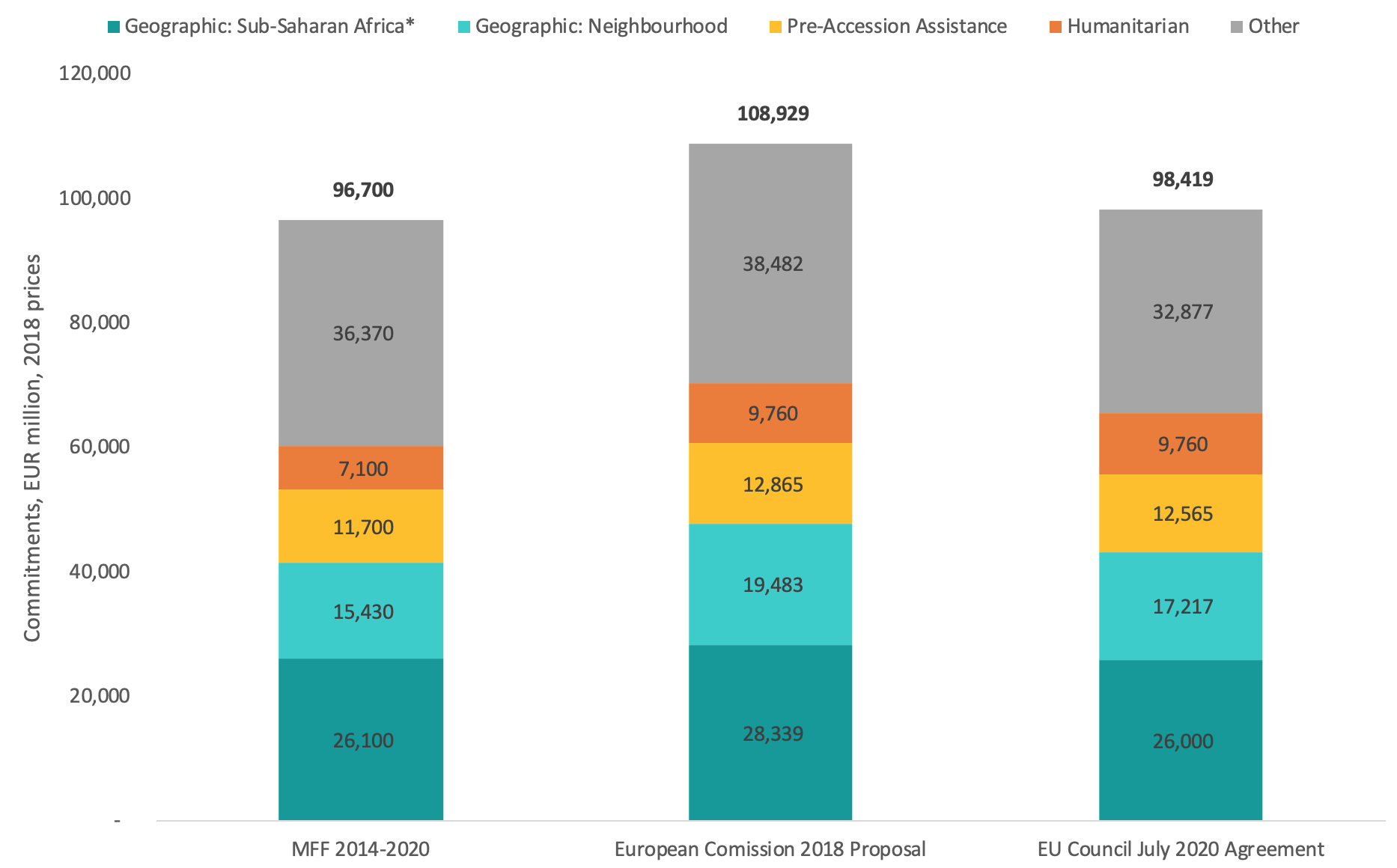

Big increases for the neighbourhood, Africa and humanitarian aid

What do the numbers tell us? Geographically, there is a whopping 43 percent increase in funding for the European Neighbourhood from €15 billion to €22 billion, with the amount ringfenced over the seven-year period. Sub-Saharan Africa also sees an increase in funding of 23 percent from €26.1 billion to €32 billion. And there is a 55 percent increase for humanitarian aid.

The instruments for human rights and democracy and peace and stability have been converted into thematic programmes and integrated into the Neighbourhood, Development, and International Cooperation Instrument, together with funding for civil society organisation and global challenges. However, overall funding for thematic priorities remains the same at €7 billion.

The flexibility cushion and the rapid response pillar are the real radicals in this budget. They consist of €10.2 billion for unforeseen events and emerging challenges such as “migratory pressures in the neighbourhood” and €4 billion for crisis response. That’s 12 percent of the entire EU external actions budget unallocated.

All of this amounts to a 30 percent increase in funding for EU external action. But where would the increase come from? The European Commission is banking on three sources, all of which are on shaky ground:

-

an increase in the member state contributions to the EU budget from 1.03 percent of GNI to 1.11 percent of GNI;

-

an increase in the EU’s own resources based on customs duties and VAT; and

-

a large reduction in funding for the Common Agricultural Policy and Cohesion Funding.

But the likelihood of the Commission having to go back to the drawing board for its external actions is high. And if it does not get the increase, it would need to reconsider both its large geographical increases and its unallocated flexibility funding, as well as its proposal of budgetising the European Development Fund for Africa, the Caribbean, and the Pacific.

Numerous priorities and heavy-handedness with earmarking and spending targets

The new EU external budget is truly global in its reach.

Source: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/budget-may2018-neighbourhood-development-cooperation_en.pdf

Least developed countries (LDCs), low income countries (LICs), as well as fragile and crisis-stricken countries are all name checked as priorities with a reiteration of the 0.2 percent of GNI target for LDCs. The EU’s thematic reach seems to be just as wide. Human rights, democracy, stability and peace are singled out and then followed by a long list of issues under “Global Challenges” including health, education, empowering women and children, migration and forced displacement, inclusive growth, decent work, social protection, and food security.

Within the new Neighbourhood, Development, and International Cooperation Instrument there are no less than four spending targets:

-

20 percent of ODA for human development and social inclusion, including gender equality and women's empowerment;

-

25 percent for climate change;

-

10 percent to tackle the root causes of irregular migration; and

-

at least 92 percent of the instrument to be reportable as ODA.

This is, once again, symptomatic of the EU spreading itself too thinly in order to satisfy member states’ engagement on development issues. EU development policy is a compromise or composite of many member states’ policies. The result: an EU development programme with an overloaded and broad agenda, operating in almost every country in the world and every sector. If only member states could work towards an agreement on an optimal division of labour based on the principles of “complementarity,” “subsidiarity,” and “comparative advantage!” Member states’ views would then be more likely to converge about how far to use the EU as their instrument of choice in development policy.

Greater autonomy for the Commission at the expense of accountability?

The new Neighbourhood, Development, and International Cooperation Instrument is like a large chest of drawers with labelled drawers for geographic and thematic priorities and a secret drawer that only the Commission holds the key to. What determines when and how the Commission decides to unlock the secret drawer?

The Commission’s stated criteria for the use of the flexibility cushion are broad and vague: unforeseen events, new needs and emerging challenges, new EU-led international priorities or initiatives, and rapid response. This gives the Commission pretty much carte blanche to use the €14 billion as it sees fit. The Commission does propose an “obligation” to inform and have regular exchanges with the European Parliament but does not foresee any co-decision role over the use of the funds. Instead, the Commission proposes setting up a Committee of member states to “assist” it and offer “opinions”. Surely the European Parliament will not accept this?

The member states and the European Parliament will now start deliberations on the Commission’s proposals. The European Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee and Development Committee will have to come together to present a united front as the external actions financial instruments are spread across both committees. The member states will also need to find their own compromise shepherded by the Bulgarian presidency of the EU.

When negotiating, all parties should bear in mind…

-

If this is the moment for the EU to rethink its place in international cooperation, then it must equip itself with a sharper development offer and sufficient funding to enable it to play a leadership role;

-

too many priorities will spread the EU too thinly and too many spending targets risk imposing arbitrary goals; and

-

while micro-management by the European Parliament should be avoided, flexibility does need to be balanced by accountability.

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise.

CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.