Recommended

Despite a broad recognition that increased access to financial services can bring significant benefits to the poor, catalyzing economic development, financial inclusion in emerging markets and developing economies continues to lag far behind expectations. Many experts and multilateral organizations have advanced policy reports and recommendations aimed at improving financial inclusion, such as the ones produced by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2016), the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructure (2016), the Global Partnership for Financial Inclusion, the Alliance for Financial Inclusion (AFI) and, Claessens and Rojas-Suarez (2016). In line with these recommendations, a large number of countries have implemented policy changes to advance digital financial inclusion. However, results are mixed. Some countries are achieving impressive inclusion gains driven by digital financial services (DFS), while in others take-up of DFS has been insufficient.

Three examples of the latter are Mexico, Pakistan, and the Philippines. These countries have put in place enabling DFS regulations and other measures (such as biometric ID systems and/or government to persons (G2P) programs) but have found moderate or little success in increasing financial inclusion. As data from Findex (2017) shows, their percentage of account ownership in 2014 and 2017 is below their corresponding regional averages. In Pakistan, financial inclusion remains extremely low; in the Philippines progress has been slow and in Mexico the level of inclusion has even decreased (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Account Ownership in Selected Countries

Note: regional averages exclude high income countries

Source: Findex (2017)

A crucial question to answer then is what else can be done to improve the effectiveness of countries’ financial inclusion strategies. In a new project by the Center for Global Development (CGD) that I lead together with Stijn Claessens from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), we propose that in designing national strategies, policymakers need to adequately prioritize their actions. To that end, we are developing a first-ever DFS decision-making tool, A Decision Tree for Improving Financial Inclusion, that will be published early next year. The Decision Tree is an analytical framework that allows a systematic identification of the most problematic constraints for financial inclusion in country-specific settings.

Many constraints can restrict financial inclusion, but to different degrees. Therefore, the Tree aims at diagnosing which constraints are binding, i.e. impeding significant improvements in the usage of DFS. Without this kind of analysis, gaps in financial inclusion frameworks may persist and policymakers may focus attention on non-binding constraints, obstacles whose solution will not deliver significant improvements unless other first-order impediments are addressed.

This project recognizes the importance of incorporating policymakers’ views. Thus, CGD, in collaboration with AFI and with the support of the Mexican Ministry of Finance, organized a workshop in Mexico City on October 10th to discuss and put into practice a draft version of the Tree with regulators from around the world. Delegations from Ecuador, Egypt, Ghana, Jordan, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, and the Philippines validated the usefulness of the Tree by applying the framework to their countries and engaging in a thoughtful exchange of views between workshop participants. Their valuable comments during the interactive sessions will undoubtedly serve to improve the Tree’s methodology. We’re confident that bringing the decision makers into the process early will have substantial impacts on the quality and applicability of our research outcomes.

But how does the Tree work?

(Conceptually, it follows Hausmann and coauthors’ (2005 and 2008) decision tree for economic growth diagnostics.)

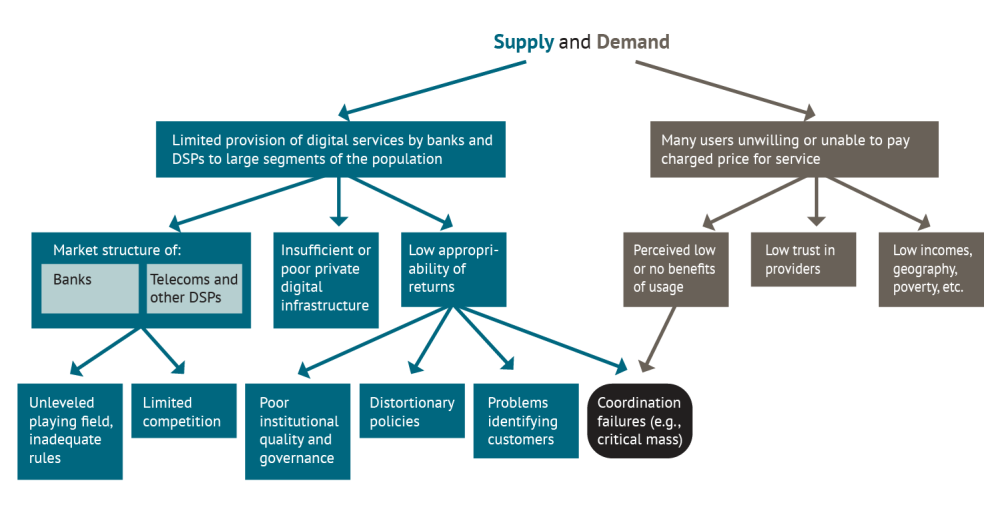

To get an idea of the functioning of the Tree, consider a country where the provision of DFS excludes large segments of the population – i.e. the usage of financial services is below its socially optimal level and, therefore, higher financial inclusion is desirable. Since low financial inclusion is the identified problem, the Tree follows a top-down approach and starts asking for the potential causes of this outcome (from the upper branches of the tree downward). Each of the potential causes in turn can be explained by additional causes (the next set of branches) and so on. Figure 2 presents a reduced and general version of the Tree for DFS.

Figure 2. Determinants of Inadequate Financial Inclusion Using Digital Means

Following basic economic analysis, the tree is built under the assumption that actual usage of financial services, including digital, is determined by supply and demand factors.

The top branches of the Tree identify three main factors that can potentially affect the supply of DFS by banks or digital service providers (DSPs): constraints arising from the market structure of the providers, low or poor provision of digital private infrastructure, and problems in appropriating returns from the offering of financial services. The Tree also identifies three factors that can potentially affect the demand for DFS: perceived low or no benefits of usage of services, low trust in providers, and the population’s low levels of income or challenging geographical settings. In turn, each of the constraints on the supply and demand side will have different causes, depicted in the lower branches of the tree.

Concretely, on the supply side, market structure refers to “the interrelation of companies in a market that impacts their behavior and their ability to make profits. Market structure is characterized by such factors as the number and size of market participants, barriers to entry and exit, and accessibility of information and technologies to all participants” (FSB (2019)). As shown in the lower branches of the Tree, two major determinants for market structure are then the degree of competition between providers and the rules under which these providers operate. Either limited competition or a regulatory environment that discriminates against some providers (an unleveled playing field) can be a major constraint for financial inclusion.

Next, there are two major reasons that could explain an insufficient provision of private digital infrastructure: either increasing the provision is not profitable for the private sector, while preserving competition, or the entry barriers are too high, either imposed by the public sector or due to market characteristics of the digital infrastructure industry (these second-tier branches are not presented in the graph due to space limitations) .

Finally, low appropriability of returns refers to the capacity of providers to capture profits, which can be hindered by: (a) distortionary policies (such as taxes on digital financial transactions), (b) poor institutional quality, (c) problems identifying customers for the purpose of satisfying internal (to the financial service providers) and government-imposed ‘know-your-customer’ requirements; and (d) the presence of coordination failures, especially when the lack of a critical mass of customers does not allow providers to reach needed economies of scale to make DFS profitable.

On the demand side, customers’ perceptions of low benefits from usage of the services can potentially be explained by insufficient knowledge or understanding of the services, while low trust in the providers can be attributed to consumer insecurity due to experiences with fraud or an unstable financial system due to large macroeconomic problems. As mentioned above, customers’ low income and the geographical distribution of these populations are additional constraints that can explain why customers do not access financial services, even if the prices of these services are low.

How to identify binding constraints

How can the analysts find which of the constraints is binding? And how do they tell whether supply or demand constraints dominate? The Tree proposes a specific approach and a set of useful indicators to answer these questions.

First, to distinguish between supply and demand constraints the analysts need to consider prices. Observing low quantities, such as the percentage of the adult population that use a service, is not enough since low usage is consistent with either low supply of or low demand for the service. As a guiding rule, one can identify the low usage of a DFS with constraints on the supply side if its price is very high relative to either another similar service or the (properly adjusted) customary price charged in other countries with equivalent levels of development. In this case, providers are only willing to supply the service at a high price (due to the presence of any of the supply-side constraints discussed above), therefore excluding large segments of the population from its use. On the other hand, low usage can be related to demand-side constraints when the price of the service is also low. In this case, even though suppliers charge low prices due to scarce demand and to attract consumers, the latter remain unable or unwilling to access and/or use DFS.

For example, data on fees charged by banks or DSP agents for the provision of payment services will help analysts in understanding whether the binding constraints are on the supply or the demand side. High fees will signal a supply-side constraint. When data on prices is not available, other indicators, such as evidence on the market behavior of a financial service following a policy change (for example, what happened to the use of a service when a tax was imposed) and survey data reflecting perceptions about services are required.

An additional and powerful indicator that a constraint is binding is if relaxing it results in significant improvements in financial inclusion. An example comes from Tanzania in 2014. Previously, interoperability between providers of mobile financial services did not exist. Signs that the lack of interoperability had become a binding constraint were mounting: (a) the market was reaching saturation from a customer acquisition perspective; (b) the initial requests for interoperability came from the industry itself; and (c) surveys revealed that 90 percent of customers would use mobile payments to send and receive money across networks if that were possible, and they were willing to pay for the service. In 2014, three of the country’s operators, Airtel, Tigo, and Zantel initially agreed to interoperate. Vodacome M-Pesa joined in early 2016. Data on interoperable transactions show a significant increase after each of the two agreements and the proportion of adults using mobile money services reached 60 percent by 2017. Taken together, the information signals that before 2014 lack of interoperability may have been a binding constraint for the growth in mobile financial services.

The Decision Tree guides analysts and authorities in the search for the reasons behind inadequate financial inclusion in an organized manner. Policymakers will navigate the branches of the Decision Tree to discover a diagnosis and, then, define the set of policy actions that best fit their country’s specific characteristics and needs. By combining evidence-based research and policymakers’ needs and inputs, this project adds a new perspective to the financial inclusion literature, offering a logical tool to support decision-makers in their complex task of improving financial inclusion.

Our next blog is focused on the workshop we organized in Mexico City, presenting our main takeaways from that collaborative effort.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Liliana Rojas-Suarez/CGD