This blog is one in a series by experts across the Center for Global Development ahead of the IMF/World Bank Spring Meetings. Each post in the series will put forward a tangible policy “win” for the World Bank, the broader MDB system, or the IMF that the author would like to see emerge from the Spring Meetings. Read the other posts in the series.

The new IMF climate finance mechanism faces multiple implementation challenges. It will take urgent actions from the institution and its major shareholders to avoid disillusionment among policymakers in climate-vulnerable developing countries.

We promised, and we delivered. This was how, last October, the IMF Managing Director characterized the operationalization of the IMF Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST), a new trust fund to help countries overcome challenges such as climate change and pandemics.

In a CGD piece published shortly after that statement, David McNair and I cautioned against prematurely declaring “mission accomplished,” before climate-vulnerable countries actually access the funds. Since the trust became operational the IMF board has approved RST-supported programs for Costa Rica, Barbados, Rwanda, Bangladesh, and Jamaica, with total lending commitments amounting to SDR 2.5 billion.

This is a welcome development, but not yet a cause for celebration. Money from the trust fund will start flowing to the above-mentioned countries only once the IMF board completes the periodic reviews of their economic programs.

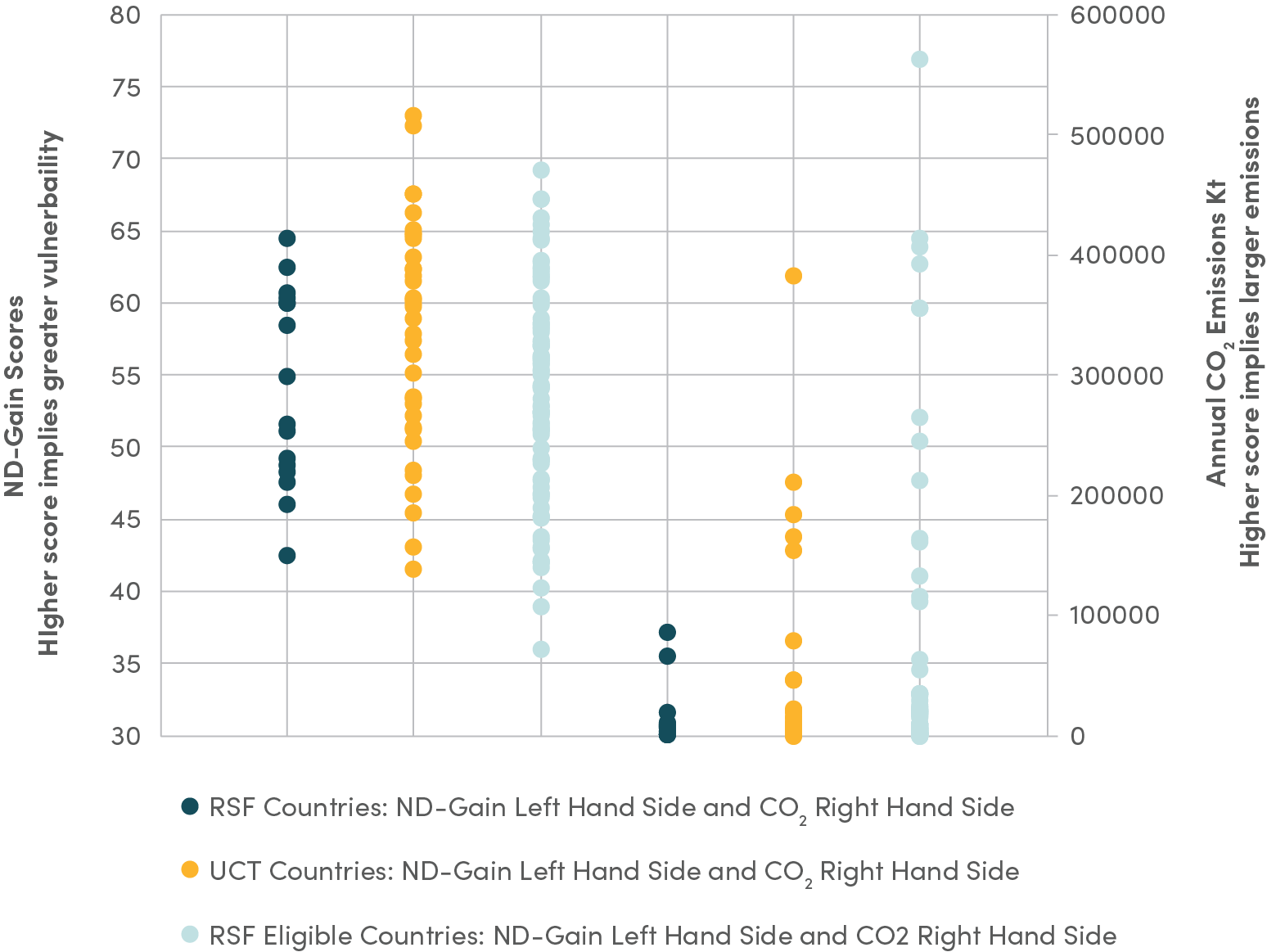

But while such disbursements are imminent in view of these reviews’ schedule, the reality is that relatively few countries among the 143 eligible ones have any reasonable hope to access these resources sooner than later.

A year and a half after the G20 backed the RST, the IMF is still struggling to reach its fundraising targets. According to the latest IMF update, total pledges secured by the RST amounted to about $40 billion, of which $26 billion have been materialized by contribution agreements. One major roadblock is the stalled congressional approval of the US Treasury’s request for permission to lend $21 billion in SDRs to the IMF trust funds for low- and middle-income countries.

In the face of insufficient funding, credit rationing appears to be a somewhat unavoidable part of the contingency measures the IMF will be forced to take. This may take not only the form of caps on the list of priority countries to be serviced by the trust, but also limits of access to available resources. Under these circumstances, many policymakers from vulnerable developing countries have voiced their frustrations over the unclear timeline, cumbersome requirements, and protracted process associated with RST access.

Furthermore, there are legitimate concerns about the IMF’s potential to provide adequate support for climate action in countries with small quota. Although maximum access under the RST is set at 150 percent of quota or SDR 1 billion, whichever is lower, these countries are notionally doomed to receive limited resources in nominal terms in an IMF program context. In addition, it is noteworthy that the IMF board has made it clear that the access norm will be 75 percent of quota.

Against this background, there is a risk that the way forward may be paved with more disillusionment among RST suitors. The G20 and the IMF must urgently take action to reverse the increasing prospects of a broken promise.

The G20 has a moral responsibility to provide the necessary support, given its decisive role in setting up the IMF climate finance toolkit. It must promptly deliver on its pledge to recycle $100 billion worth of SDRs, thus enabling the IMF to reach—and ideally exceed—its fundraising target. To begin it is urgent for key Group members to finalize additional contribution agreements with the IMF under the RST. As part of this effort the US should play a leading role, even though the current dynamics of domestic politics leaves little hope for any imminent breakthrough.

However, support to the IMF should not be provided with no strings attached. In exchange for that support, the institution must be called upon to take internal measures to mobilize resources for the RST. For instance, it should discontinue the payment of fees to its main account—the General Resource Account—to cover trust management activities. The G20 would also do a service to itself and low-income and climate-vulnerable countries by making the full fulfillment of its pledge conditional on loosening RST access limits for countries with small quota and large climate-related vulnerabilities.

The IMF should be encouraged to promptly finalize the establishment of a coordination framework for pandemic preparedness and response in partnership with the WHO, the World Bank, or any multilateral organization with relevant expertise in this area. In so doing, it will not only meet fully the objectives of the RST, but also provide a much-needed boost to ongoing efforts to upgrade the global financial architecture and enhance its ability to support improved delivery of global public goods.

Finally, the IMF should not be granted the monopoly of using recycled SDRs. Multilateral development banks should be allocated part of these reserve assets with the aim of boosting their capacities for supporting climate action. The IMF-World Bank Spring Meetings taking place this week in Washington will be a critical opportunity to make headway in this direction, particularly in the case of the African Development Bank.

The IMF promised, but it has not yet fully delivered. It will probably not unless it receives timely and conditional support from the global community.

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise.

CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.