The 2018 Summit of the Forum on China Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) will open next week in Beijing. About 50 African heads of state are scheduled to participate. Launched in 2000 and held every three years, FOCAC is the linchpin of Chinese foreign policy in Africa and the fulcrum of its investment and lending on the continent.

There is much speculation about the size of the investment package China will unveil at the summit. At the last FOCAC summit, it announced a $60 billion package for Africa comprised of $35 billion in preferential loans and export credit lines, $5 billion in grants, $15 billion of capital for the China-Africa Development Fund, and $5 billion in loans for the development of African small and medium enterprises.

It appears, however, that we are in a new phase of Chinese financing. A combination of domestic and international pressures will likely alter China’s extensive lending program—African states that have relied on this lifeline must adjust to the new reality.

Any reduction in Chinese lending, however, must be construed in the context of a very high baseline; financing is not going to disappear. And the new reality could benefit African countries by compelling improved project preparation and implementation, reducing price inflation, and decreasing the role of political over economic considerations in project selection.

Debt Trap or Much-Needed Investment?

China’s role in Africa’s emerging debt crisis has attracted significant attention. China is now routinely accused of “debt trap diplomacy,” or intentionally “miring supposed partners, particularly developing countries, in unsustainable debt-based relations.” The assumption seems to be that “China’s own economic and geostrategic interests are maximized when its lending partners are in distress.”

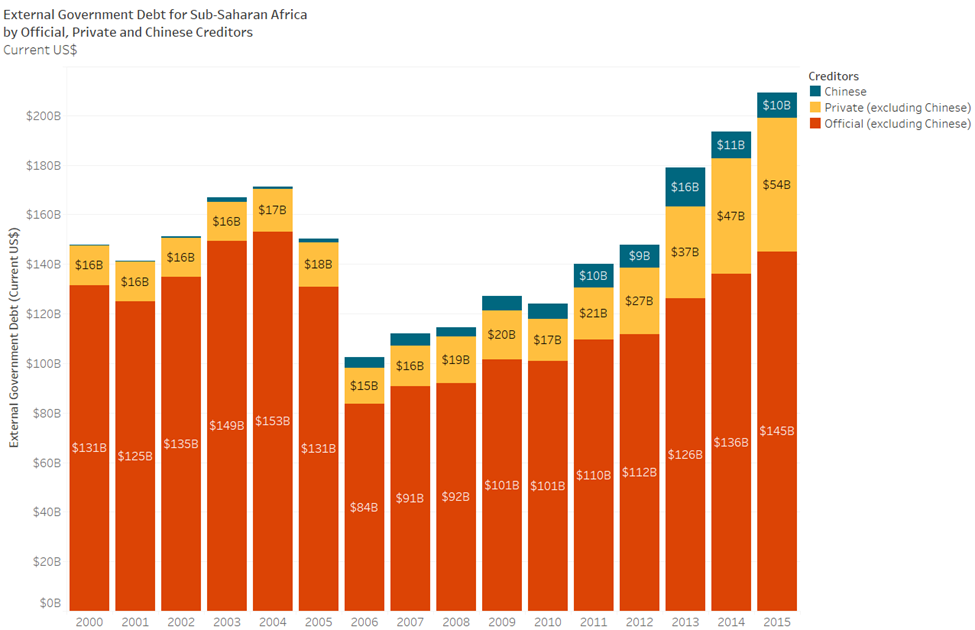

The debt trap diplomacy case, however, has never been convincingly argued and its application in Africa is, at best, tenuous. The reality of Africa’s debt to China is not particularly remarkable when taken against the sources of continent’s external debt stock (see figure below). A number of African countries’ (Djibouti, Kenya, and Angola) debt obligations to China are alarming—as they would be regardless of creditor. China’s $115 billion credit to Africa between 2000 and 2016 is still less than 2 percent of the total $6.9 trillion of low and middle income countries’ debt stock. Recent studies have show that China is not a driver of debt distress in Africa—yet. The language of debt trap diplomacy resonates more in Western countries, especially the United States, and is rooted in anxiety about China’s rise as a global power rather than in the reality of Africa.

For Africa, Chinese financing—and by extension, FOCAC—remains an indispensable option. During my tenure as an official of the government of Liberia, I remember the long preparation meetings for FOCAC. This certainly was not unique to Liberia. Africa will continue to look to China for the foreseeable future as a source of funding. The Population Reference Bureau projects that Africa will be home to 58 percent of the projected 2.6 billion increase in global population between now and 2050. Africa is not creating jobs anywhere near the pace needed to accommodate those numbers. It also lags behind all other regions of the world on every measure of infrastructure coverage. This has led to tepid industrial growth, with Africa’s share of global manufacturing falling from about 3 percent in 1970 to less than 2 percent in 2013.

Furthermore, official development assistance and remittances have declined and are falling across Africa. Across Europe and the United States, nativist political parties and racist politicians, some openly hostile to Africans, are either winning elections or comprising significant parliamentary blocs. Therefore, investment from China is one of the few ways African countries can get financing for the infrastructure it so desperately needs.

China has financed more than 3,000 strategic infrastructure projects in Africa and extended tens of billions of dollars in commercial loans to African governments and state-owned enterprises. China’s export of excess industrial capacity and its model of special economic zones has benefited the nascent manufacturing sector on the continent. An in-depth evaluation of Africa’s economic partnerships with the rest of the world in trade, investment stock, investment growth, infrastructure financing, and aid concluded that no other country matches the depth and breadth of Chinese engagement.

Will China be Forced to Curb its Ambition in Africa?

It appears, however, that a combination of domestic and international pressures—both economic and political—will limit Chinese ambition, at least as expressed through extension of credit.

Domestic Pressures

China watchers see “obvious signs of discontent” with President Xi’s policy agenda, including Chinese spending in Africa. Matt Schrader notes that “BRI lending has already begun to shrink, decreasing dramatically since 2015” and that if it were “to decrease further, it would have important strategic repercussions throughout the Eurasian landmass and Africa.” Schrader suggests a link between emerging criticism of the expansive BRI (the Belt and Road Initiative, an infrastructure plan spanning Asia, Europe, and Africa), which its domestic Chinese critics have taken to calling “aid,” and the reduced ambition of the program.

As China’s trade war with the United States escalates, the People’s Bank of China is attempting a balancing act between allowing the yuan to weaken against the dollar and intervening to arrest the decline before it leads to a devaluation that would affect the Chinese economy. And this trade war is occurring as China attempts to manage its massive domestic debt. China’s debt “ballooned from about $6tn at the time of the financial crisis [2008] to nearly $28tn by the end of last year.” This has created an asset bubble and there is foreshadowing of a crisis of sorts. Even if a crisis does not emerge, managing this debt will remain a prominent focus of Chinese policymakers.

International Pressures

China is facing pressure to conform to international lending standards. The IMF is committed to outreach to the Chinese Ministry of Commerce, the China EXIM Bank, and the China Agricultural and Development Bank about coordination around the principles of the Paris Club (PC) on debt sustainability. Accepting PC or PC-lite debt sustainability rules will significantly affect Chinese lending, especially in Africa.

The rising chorus of China’s debt trap diplomacy, and the narrative of weaponizing loans, are beginning to spread. For example, 16 American senators wrote a letter to Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo inquiring “how can the United States use its influence to ensure that [IMF] bailout terms prevent the continuation of ongoing BRI projects, or the start of new BRI projects?” The incident with the Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka—unable to service massive debt to China, the Sri Lankan government was forced to sign over a 70 percent stake in the port to China for 99-year lease—is paraded as evidence of China’s bad intent in providing loans to low-income countries. Domestic politics in partner countries is also beginning to affect Chinese lending, with Malaysia canceling two large Chinese projects after elections brought a new government to power. It is also possible that Chinese policymakers, faced with the possibility of non-performing loans and possible default, are being pragmatic.

What Does This Mean for FOCAC?

It is in this environment that 50 African heads of state will meet with their Chinese counterparts at this year’s FOCAC summit. What can we expect from the summit?

It is my view that there will be no visible difference from previous FOCAC summits. China will likely announce a massive loan and investment package for Africa at this summit as it has in past years. Under Xi Jinping, China has increased its focus on emphasizing “discursive power” and making China’s voice heard on a global level. Nothing will change here, especially since this FOCAC comes during the fifth anniversary of BRI. China will be determined to assure its African partners that it remains a stable and dependable ally. This will be even more important as Chinese leadership attempts to contrast itself with its American counterpart.

But the pressures outlined above cannot be ignored, so we will expect to see changes in the criteria against which eligible project are evaluated. It will not be surprising if the downward trend of BRI investment continues and if FOCAC financing comes with a higher bar for project eligibility.

This is not necessarily a bad thing. We now know that Kenyan officials siphoned off billions in Kenyan shillings from Chinese loans for a standard gauge railroad project through elaborate fraudulent land payment schemes. There are still questions about the true cost of the project and whether Kenya overpaid. A set of stricter project eligibility criteria could lead to more competent project preparation and implementation, and to reduced price inflation. It could also decrease the incidence of projects selected for funding based on electioneering and politics rather than on social and economic policy outcomes.

African states will continue to look toward FOCAC and Chinese lending as a significant component of the suite of tools available to deal with poverty and the gap in infrastructure financing. But they will be required to adjust to the new reality in which the Chinese spigot, while not completely turned off, has slowed as China adjusts to pressures at home and abroad.

Thanks to Asad Sami and Kelsey Ross for research assistance.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.