The global education community has been calling on poor countries to increase their spending on education for years now, to little avail. The share of government budgets in low-and middle-income countries going on education has barely crept up, from 15.2 percent in 2000 to 15.9 percent in 2014. Instead of repeatedly making the case for how important education is, or calling for political will, a smarter approach could be to directly address the political economy of education spending. The most direct and immediate beneficiaries of education—children—don’t even get to vote. And if they did, there is a good chance that they would vote for more spending on their own day-to-day lives—at school.

The political economy of education

Literature on the political economy of education often focuses on the role of parents in holding schools and government to account for service provision. But often it is students themselves who take decisions about their education.

When it comes to government spending, evidence from the United States shows that jurisdictions with larger elderly populations spend less on education. Conversely, efforts to ease registration of young people have led to higher education spending. Allowing voters to pre-register for elections increased the share of young people who actually voted. Each one percent increase in youth voting led to a roughly one percent increase in education spending. Historically, the extension of the franchise to women led to substantial increases in social spending. Historical data from Western Europe shows a short-term increase in social spending of around one percent of GDP after women gained the right to vote. In Switzerland social spending increased by 28 percent. In the United States, state taxes and spending increased by 10 percent, and spending on healthcare increased.

Several countries have lowered their voting age to 16 in recent years, but no studies have yet looked at the effect of this change on education spending. But we can expect that any effect would depend on:

- The degree to which the young have different preferences

- The size of the new youth vote compared to the size of the electorate

Policy preferences of the young

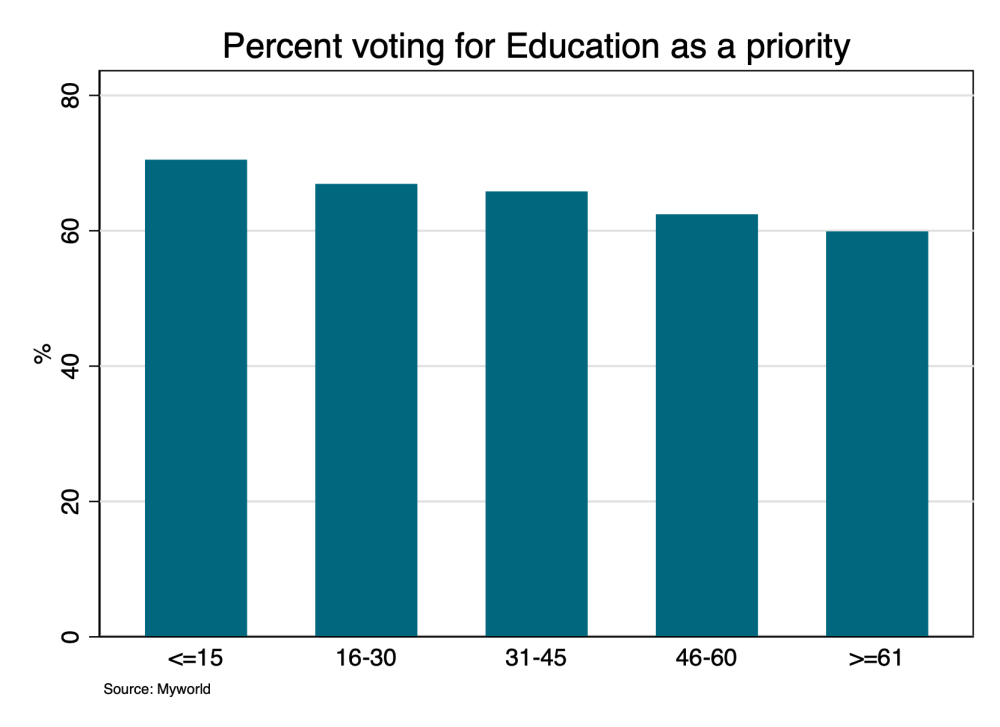

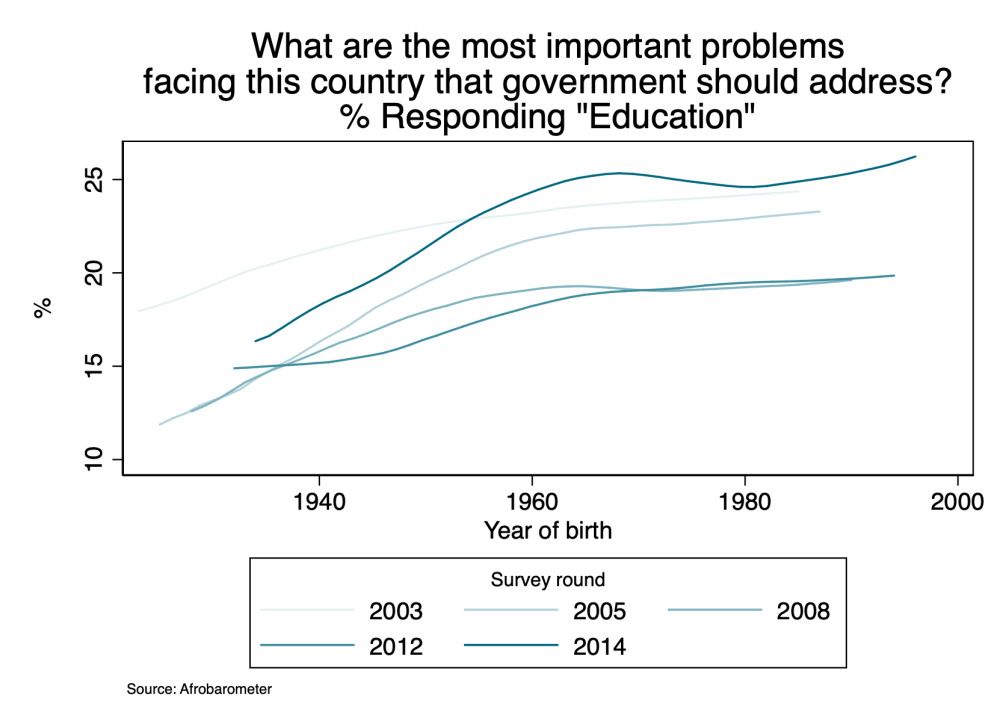

Survey data on the political preferences of young people in poor countries is scarce, but there is some. First, in the UN’s global online poll of SDG priorities “MyWorld,” people aged 15 or younger were more likely to prioritise education than older people.

How big is the youth vote?

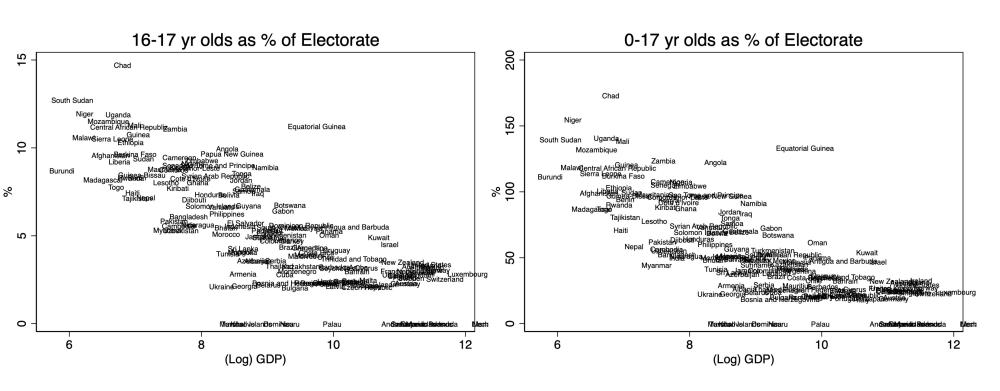

There is remarkable consistency in the voting age of countries around the world. In 207 countries (88 percent), the voting age is 18. This global norm effectively dis-enfranchises the majority of the population in many poor countries. The relatively young age structure of most developing countries implies a large share of the population would be enfranchised by a lower voting age. Giving all children the vote would lead to a doubling of the size of the electorate in many countries. But even just 16-17-year-olds would lead to a 10 percent increase for many countries.

The figures below show the relationship between country income, and the share of the electorate made up by young people.

Source: IDEA Voter Turnout Database, IPUMS Population data, World Bank GDP data

Effects on spending

The estimated elasticity of spending with respect to changes in youth voting from the United States (as discussed above) wouldn’t necessarily hold in other countries, but it’s perhaps the best estimate we have. If it did, just giving 16-17-year-olds the right to vote has the potential to lead to a substantial ~10 percent increase in public education spending. That’s a similar order of magnitude to foreign aid spending on education.

Is such a change actually realistic or practical?

Several countries have lowered the voting age to 16 already (Argentina, Austria, Bosnia, Brazil, Cuba, Ecuador, Guernsey, Isle of Man, Jersey, Malta, Nicaragua, and Scotland). Lowering the voting age to 16 is the official policy of the UK opposition Labour Party, as well as US Democratic Party Presidential Candidate Andrew Yang. Some have gone further, arguing that all children should get the vote, with parents casting it on their behalf until they are able to make an independent choice (for example John Quiggin recently, and before him UK think tank DEMOS back in 2003). Last year, the head of politics at Cambridge University suggested lowering the voting age to six, in order to try and make modern democracy more equitable for the young.

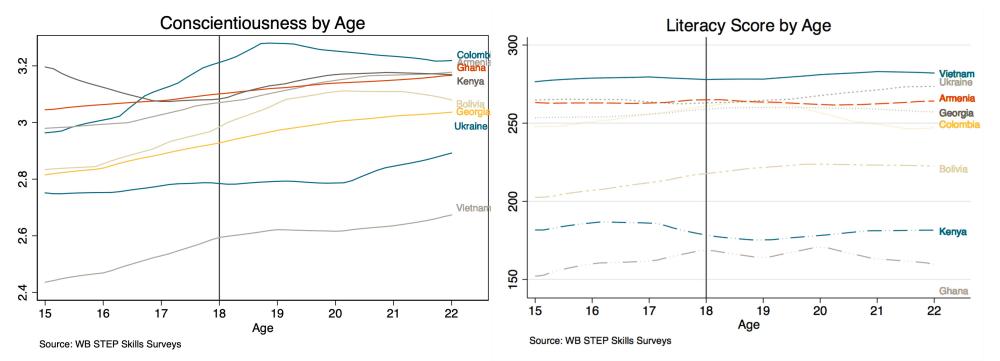

One thing that is clear: nothing special that happens at age 18. Using data for urban adults age 15+ in eight low and middle-income countries, I show in the figures below that there is no jump in scores at age 18 for conscientiousness or for reading skills.

Similarly, the 2017 round of India’s ASER survey shows no clear difference between the reading and mathematics ability of 18-year-olds and 14-year-olds.

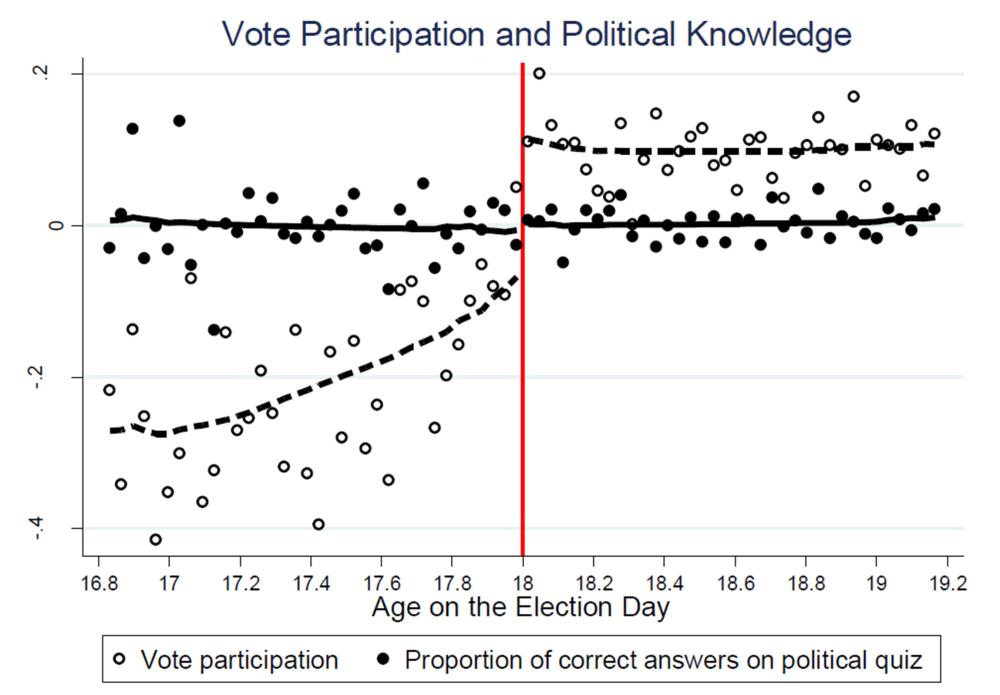

What about political knowledge? In Brazil, 16-year-olds are eligible to vote, but voting only becomes compulsory at age 18. Fernanda L L de Leon and Renata Rizzi show that there is no discontinuity at age 18 in political knowledge or media consumption. Similar results have been found in Austria where the voting age is 16. Those under 18 are no less interested in or knowledgeable about politics.

Source: Fernanda L L de Leon and Renata Rizzi

So, if nothing magical happens at age 18, then what age is appropriate to vote? Modern neuroscience shows that children develop different parts of their brain at different times. Self-regulation might continue developing until age 22, but even young adolescents can engage in cold hard logic as well as an adult. There are a range of thresholds we use for deciding who is a child and who has adult rights and responsibilities—criminal responsibility, the right to drive, drink, smoke, have sex, get married, join the army, get a job, pay taxes. One particularly relevant threshold is when you can work and pay taxes—“no taxation without representation” as the saying goes. The UN convention that sets out the general minimum age for working puts it at 15, or 13 for “light work,” and with the allowance for countries to reduce both by one year “where the economy and educational facilities are insufficiently developed.” So, the UN says its ok for 12-year-olds to do light work in some developing countries.

That’s six years before they’ll be able to vote.

The case for voting rights for children is not just an instrumental one

Aveek Bhattacharya outlines a series of philosophical principles. Voting is not just about the skill of the voter, but about the representation of diverse interests. It also educates, by providing people with the opportunity to engage in the political process. Voting matters for individual autonomy. In addition, early voting encourages later participation. in countries where 16- and 17-year-olds are allowed to vote, they are more likely to vote than 18-19-year-olds. This matters particularly because the first experience of voting (or not) tends to predict future voting habits, so setting off on the right foot can increase participation overall.

There is a credible philosophical case to be made that giving children the right to vote is the right thing to do regardless of the consequences. It’s really a bonus that doing the right thing might also have positive consequences for the allocation of government spending.

There are plenty of campaigns to lower the voting age in high-income countries, and very few in poorer countries. Advocates for global education and for children’s rights could do worse than to think about whether they should be campaigning for giving children the right to vote too.

Image credit for social media: Source: Fernanda L L de Leon and Renata Rizzi

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.