Recommended

WORKING PAPERS

Early in the COVID-19 outbreak, experts warned of increased violence against women and children (VAW/C). In China’s Jianli County, for example, the local police station reported receiving 162 reports of intimate partner violence in February—three times what was reported in February 2019. Existing research about pandemics and disease outbreaks unfortunately aligns with the increased violence stemming from COVID-19 and related response efforts. Understanding why this happens is critical to inform policy and program responses to mitigate adverse effects.

In a new CGD working paper, we explore the broad literature from past pandemics, public health emergencies, and other crisis settings to identify the pathways through which pandemics can incite or exacerbate various forms of VAW/C. Drawing on the evidence, we offer eight recommendations for governments, civil society, and international and community-based organizations to help make women and children safer when the next emergency hits.

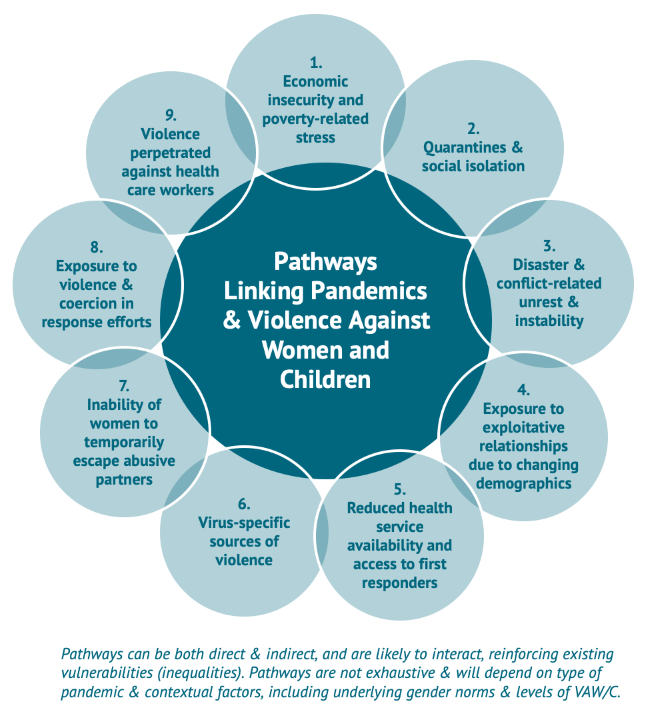

The pathways to violence

We identify at least nine ways in which the consequences of and responses to pandemics like COVID-19 can lead to or increase VAW/C:

Economic insecurity and poverty-related stress: Poverty-related stress and economic insecurity correlate with poor coping strategies (e.g., substance abuse) can lead to increases in intimate partner violence and child maltreatment. When unemployment rates skyrocket and economies slow to a halt, VAW/C is likely to increase as a result of related stress.

Quarantines and social isolation: Close quarters, especially those tied to stressful conditions, are linked to stress, fear, poor mental health, and disorders, which can in turn increase the likelihood of VAW/C. Evidence focused on other crisis settings, including refugee camps and humanitarian assistance zones, confirms that when family members are in close proximity under conditions of duress for extended periods of time, rates of VAW/C are high. Quarantine also increases face-to-face exposure to perpetrators and can reinforce abuse tactics of social isolation.

Disaster- and conflict-related unrest and instability: Pandemics can break down social infrastructure, compounding existing weaknesses in conflict and disaster settings. This may lead to increased family separation, intra-familial violence, and exposure of women and children to unsafe conditions, including exposure to sexual violence and harassment as they seek to obtain basic goods, including food, firewood, and water.

Exposure to exploitative relationships due to changing demographics: Higher mortality rates drive extended family networks to care for orphans who have lost their parents to disease, creating new strains on households and risking a decreased quality of care, and even violence, directed at children. Changing family structures, combined with school closures and financial duress, can result in higher rates of exploitative, transactional sex among adolescent girls and higher fertility rates, with longer-term consequences for increased VAW/C.

Reduced health service availability and access to first responders: Health providers and emergency first responders are often the first point of contact for survivors, as well as sources of short-term physical protection for women and children. With all hands on deck needed to respond to pandemics, first responder resources and referral pathways that survivors rely on may not be available unless, following France’s example, intentional efforts are made to provide accessible points of assistance. In addition, women may avoid seeking health services for physical abuse and injuries, for fear of possible infection.

Virus-specific sources of violence: The COVID-19 pandemic has already documented ways perpetrators are using virus-specific misinformation and scare-tactics, as well as controlling behaviors to withhold safety items. In other pandemics, including the HIV/AIDS, violence has been linked to disclosure of serostatus, or may increase risk of lifelong exposure to violence due to coinciding disabilities (e.g. microcephaly within the Zika outbreak).

Inability of women to temporarily escape abusive partners: Women already face complex decisions and a wide range of barriers preventing their ability to safely escape abusive partners. In times of pandemic, when mobility is constrained, social distancing measures are imposed, economic vulnerability increases, and legal (social services) are scaled back, challenges in temporarily escaping abusive partners are exacerbated.

Exposure to violence and coercion in response efforts: There have been documented cases of aid workers responsible for assisting vulnerable populations in times of crisis committing acts of violence against women and children. Unequal power dynamics open up possibilities for those meant to help—including, as seen in the Ebola response, health workers, taxi drivers, and even burial teams—to pressure populations into exploitative relationships in exchange for transport, food, cash, and vaccines.

Violence against health care workers: Women make up nearly 70 percent of the global health workforce and are regularly subjected to abuse and harassment from colleagues and patients. Risks may be heightened in pandemic settings, harming women themselves and the crippling the effectiveness of broader health systems.

What can be done to make women and children safer during a pandemic?

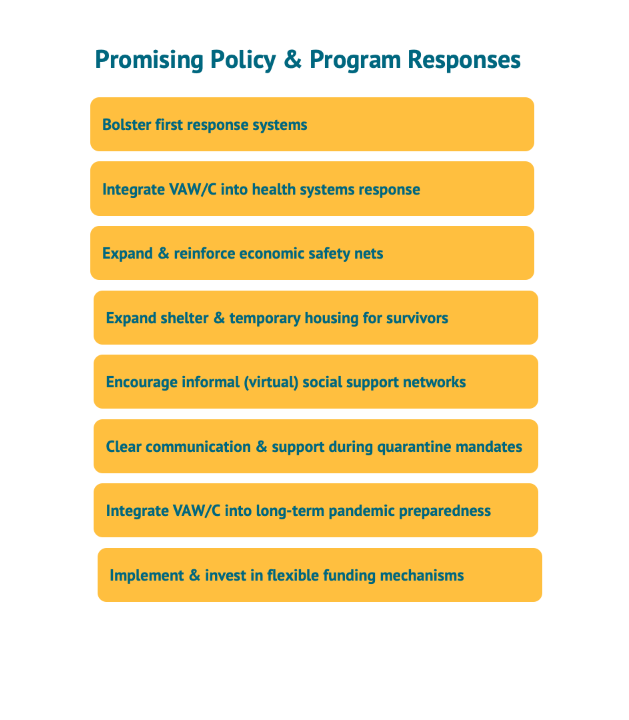

We propose the following actions by governments, civil society, and international and community-based organizations:

-

Bolster violence-related first-response systems: First-responders should anticipate a surge of VAW/C at the outset of pandemic outbreaks and prepare accordingly, including through increasing staff and support resources. Wherever possible, virtual (and free-of-charge) options for mental health support, legal counsel, and other services should be instituted.

- Ensure VAW/C is integrated into health systems response: Health care providers should be trained in identifying women and children at risk of violence present in all testing and screening locations, such that recommendations for “self-quarantine” or “shelter at home” are accompanied by an assessment of the safety of doing so. In parallel, health systems must institute protections for female health workers to mitigate risks of sexual harassment and violence.

- Expand and reinforce social safety nets: Proposals for rapid expansion of gender-sensitive social safety nets, including paid sick leave, unemployment insurance, direct cash or food voucher payments, and/or tax relief are all immediate options—with emphasis on pro-poor or universal schemes of sufficient monetary value.

- Expand shelter and temporary housing for survivors: There is need to ensure pandemic-safe surge housing available for women and children at high risk of violence in their homes. For example, the Canadian government announced a $82-billion COVID-19 aid package on March 18, which included earmarked increases in $50 million funding for gender-based violence shelters and sexual assault centers.

- Encourage informal (and virtual) social support networks: Within the contexts of pandemics, there are a number of options to scale-up and leverage existing online and virtual platforms for online support networks. In settings without options for online platforms, options for text-based (i.e., WhatsApp) networks can be encouraged, building on existing women’s groups and collectives.

- Clear communication and support during quarantine mandates: While quarantines and self-isolation are often a necessary public health response to pandemics, they also come with significant costs to populations’ physical and mental health. Officials should quarantine individuals for no longer than required, providing a clear rationale for quarantine and information about protocols, and ensuring there are sufficient supplies of goods and essential services to populations under isolation.

- Integrate VAW/C programming into longer-term pandemic preparedness: VAW/C should be integrated into disaster risk reduction and preparedness, as well as pandemic preparedness. Preparedness efforts should incorporate a gender and age lens throughout, ensuring women and children are included in preparedness processes and decision-making. Both One Health and Global Health Security Agenda are prime entry points to integrate VAW/C programming.

- Implement and invest in flexible funding mechanisms: In times of uncertainty and crises, multilateral and bilateral donors, as well as philanthropic donors, should allow for flexible funding. This includes provisions to allow funding to be allocated away from contractual requirements and to operating (overhead) expenses with decreased reporting requirements, as spearheaded by the Ford Foundation in the context of COVID-19. Increased flexibility can allow grantees to prioritize increased and gender-responsive investment to curb the full array of risks brought on by pandemics, including heightened VAW/C.

Better data and evidence can bolster the efficacy of these responses. Because the evidence on VAW/C in pandemic contexts is limited, we call for more research that will allow us to better understand the magnitude of the problem, clarify the pathways driving changes in violence and linkages with other social and economic factors, and directly inform specific intervention and response options. We hope our new CGD working paper serves as a starting point to inform COVID-19 response efforts, preparedness efforts for future pandemics, and efforts to combat VAW/C and support survivors more broadly. If the international community does not act to mitigate risk in the current pandemic and use it as a learning opportunity, women and children will pay the price, both now and in the future.

We thank our co-authors (Kelly Thompson, Niyati Shah, Sabine Oertelt-Prigione and Nicole van Gelder), members of the Gender and COVID-19 Working Group for their thoughtful comments and recommendations, Shelby Bourgault for research support, and the CGD communications team.

Disclaimer

CGD blog posts reflect the views of the authors, drawing on prior research and experience in their areas of expertise. CGD is a nonpartisan, independent organization and does not take institutional positions.

Image credit for social media/web: Images of Empowerment